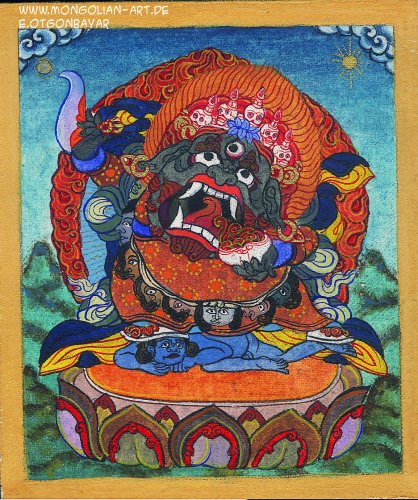

| Demon-02 (thangka, thanka, tanka painting) Tempera on cotton, 8 x 9,5 cm, Year 1999 Thangka A "Thangka," also known as "Tangka", "Thanka" or "Tanka" (Nepali pronunciation: [ˈtʰaːŋkaː], the 'th' as the aspirated 't' of top and the 'a' as in the word father) (Tibetan: ཐང་ཀ་, Nepal Bhasa: पौभा) is a painted or embroidered Buddhist banner which was hung in a monastery or a family altar and occasionally carried by monks in ceremonial processions. In Tibetan the word thang means flat, and thus the Thangka is a kind of painting done on flat surface but which can be rolled up when not required for display, sometimes called a scroll-painting. The most common shape of a Thangka is the upright rectangular form. Originally, thangka painting became popular among traveling monks because the scroll paintings were easily rolled and transported from monastery to monastery. These thangka served as important teaching tools depicting the life of the Buddha, various influential lamas and other deities and bodhisattvas. One popular subject is The Wheel of Life, which is a visual representation of the Abhidharma teachings (Art of Enlightenment). To Buddhists these Tibetan religious paintings offer a beautiful manifestation of the divine, being both visually and mentally stimulating. Thangka, when created properly, perform several different functions. Images of deities can be used as teaching tools when depicting the life (or lives) of the Buddha, describing historical events concerning important Lamas, or retelling myths associated with other deities. Devotional images act as the centerpiece during a ritual or ceremony and are often used as mediums through which one can offer prayers or make requests. Overall, and perhaps most importantly, religious art is used as a meditation tool to help bring one further down the path to enlightenment. The Buddhist Vajrayana practitioner uses a thanga image of their yidam, or meditation deity, as a guide, by visualizing “themselves as being that deity, thereby internalizing the Buddha qualities (Lipton, Ragnubs).” Historian note that Chinese painting had a profound influence on Tibetan painting in general. Starting from the 14th and 15th century, Tibetan painting had incorporated many elements from the Chinese, and during the 18th century, Chinese painting had a deep and far-stretched impact on Tibetan visual art.[1] According to Giuseppe Tucci, by the time of the Qing Dynasty, "a new Tibetan art was then developed, which in a certain sense was a provincial echo of the Chinese 18th century's smooth ornate preciosity."[1] History Thangka is a Nepalese art form which was imported to Tibet after Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal, daughter of Lichchavi king, married with Sron Tsan Gampo, the ruler of Tibet [2][3] imported the images of Aryawalokirteshwar and other Nepalese deities to Tibet [4]. Types of thangkas Based on technique and material, thangkas can be grouped by types. Generally, they are divided into two broad categories: those which are painted (Tib.) bris-tan and those which are made of silk, either by appliqué or with embroidery. Thangkas are further divided into these more specific categories:

Thangkas are made on various fabrics. The most common is a loosely woven cotton produced in widths from 40 to 58 centimeters (16 - 23 inches). While some variations do exist, thangkas wider than 45 centimeters (17 or 18 inches) frequently have seams in the support. Process Painted thangkas are done on cotton canvas or silk with water soluble pigments, both mineral and organic, tempered with a herb and glue solution - in Western terminology, a distemper technique. The entire process demands great mastery over the drawing and perfect understanding of iconometric principles. The composition of a thangka, as with the majority of Buddhist art, is highly geometric. Arms, legs, eyes, nostrils, ears, and various ritual implements are all laid out on a systematic grid of angles and intersecting lines. A skilled thangka artist will generally select from a variety of predesigned items to include in the composition, ranging from alms bowls and animals, to the shape, size, and angle of a figure's eyes, nose, and lips. The process seems very scientific, but often requires a very deep understanding of the symbolism of the scene being depicted, in order to capture the essence or spirit of it. Thangka are often overflowing with symbolism and allusion. Because the art is explicitly religious all symbols and allusions must be in accordance with strict guidelines laid out in buddhist scripture. The artist must be properly trained and have sufficient religious understanding, knowledge and background in order to create an accurate and appropriate thangka. Lipton and Ragnubs clarify this in Treasures of Tibetan Art: “[Tibetan] art exemplifies the nirmanakaya, the physical body of Buddha, and also the qualities of the Buddha, perhaps in the form of a deity. Art objects, therefore, must follow rules specified in the Buddhist scriptures regarding proportions, shape, color, stance, hand positions, and attributes in order to personify correctly the Buddha or Deities.” References

|