1911-2017

Mongolian Scientific and Research Institute for National Freedom

The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Mongolia

Ulaanbaatar 2018

The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Mongolia

Ulaanbaatar 2018

THE HISTORY OF MODERN MONGOLIA 1911-2017

The fall of Communism in the 1980s, leading to the Democratic Revolution in the 1990s, resulted in drastic changes in Mongolia’s societal perspective. Since that time, 28 years have passed, yet almost no difference can be seen between the written history of today and that of the past, when the whole of Mongolian society was driven by Soviet ideology. We are misinforming Mongolia’s post-Democracy generations, by passing along those written histories and literature, steeped as they are in this ideology.

Our book is written as a corrective to this situation; it presents Mongolia’s history during this period, without the influence of ideology because we believe Mongolians deserve to know their own path, to better understand their situation today. We have attempted to write a comprehensive history book with fresh eyes, based on scientific research evidence.

It is our fervent hope that the information contained herein will benefit everyone interested in the history of modern Mongolia.

© Mongolian Scientific and Research Institute for National Freedom

THE HISTORY OF MODERN MONGOLIA 1911-2017

PREFACE

It is a great honor to write the preface of this book, which attends to the recent history of Mongolia. With this publication, the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) Mongolia follows the advice of its eponym, Konrad Adenauer, who viewed the examination of the past as a requirement to shape the future.

The first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany’s name and principles are our guidelines, duty, and obligation. Established in 1955 as “Society for Christian-Democratic Civic Education”, the Foundation took on the name of the first Federal Chancellor in 1964. At home as well as abroad, our civic education programs aim at promoting freedom and liberty, peace, and justice. We focus on consolidating democracy, the unification of Europe and the strengthening of transatlantic relations, as well as on development cooperation.

Our offices abroad are in charge of over 200 projects in more than 120 countries. The foundation’s headquarters are situated in Sankt Augustin near Bonn, and also in Berlin. There, an additional conference center, named “The Academy”, was opened in 1998. In 1993, KAS established its office in Ulan Bator. To foster peace and freedom we encourage a continuous dialog at the national and international levels as well as the exchange between cultures and religions.

The book “The History of Mongolia (1911-2017)”, written in collaboration with the “Mongolian Scientific and Research Institute for National Freedom”, is worth reading by the history student as well as anyone with a general interest in history. It provides a clear and informative guide to the twists and turns of Mongolian history.

FOREWORD

Since the Democratic revolution, archives of Mongolia and Russia that were once private have opened for public review, leading to the publication of many documents related to the history of Mongolia in the 20th century. In addition, people’s oral stories and historical memories are starting to emerge now, as their desire to know their history, especially 20th century history, is flowering. However, the amount of research being done with these archival documents seems low in Mongolia. Thus, this book is an attempt to write the history of Mongolia from 1911 to 2017, without any ideological influence.

During the Socialist period, our history could not be called ‘Mongolian history;’ instead, we were to name it the history of the “Mongolian People’s Republic,” the term given to us in 1924 due to Soviet presence here. Under this terminology, thousands of records of written history were distorted, due to the participation of those Soviet scientists who formulated the ideologies, in concealing underlying facts and realities.

Mongolia has been passing along ideologically-fuelled viewpoints on social stratification, politics, history and traditions, thus providing innacurate information to Mongolians. To give an example, Mongolian people believe that the history of modern Mongolia began from the People’s Revolution of 1921, an ideological reflection of Soviet ideology because it reflected a date after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia. But, according to the historical sources, the beginning of modern Mongolia is marked, indisputably, by the 1911 revolution.

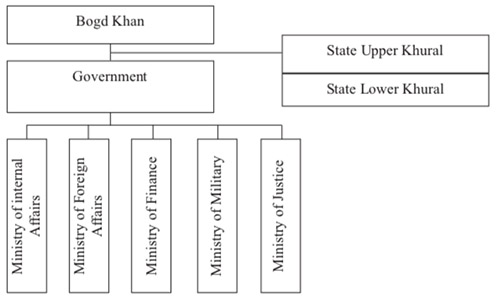

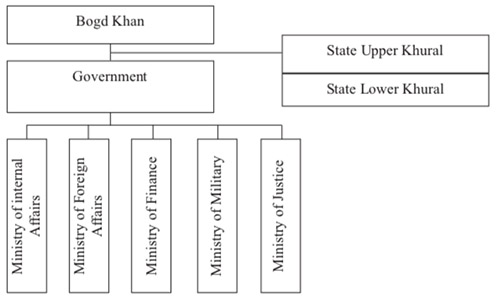

This book covers the modern history of Mongolia, beginning with the revolution for independence from the Manchu-Chinese empire declared in 1911, through to 2018. It is divided into the following periods: Rebirth of the Bogdo Khanate in Mongolia 1911-1919; Mongolia during the Constitutional Monarchy period 1921-1924; Mongolian People’s Republic 1924-1990; and the Democratic period in Mongolia from 1990 to today. For ease of comparison, each period has a section for politics, economics, foreign affairs, society, culture and education. This standard structure was intented to eliminate any bias toward real events and historical figures; it relies only on archival sources for validitation. The objective of this book is to change the conservative and conventional mindset of people toward Mongolia’s modern history, by providing fact-based evidence. For instance, the story of Choibalsan, the respected minister who could arguably be called the ‘Mongolian Stalin,’ is not what it seemed.

In order to present a historical biography, we aimed to evaluate the individual as a social entity, as well as the people of Mongolia. It is important to note that Mongolians have true meaning in the history of their journey, and telling these stories truthfully will edify future generations.

This book also aims to answer questions such as: what are the stories of Mongolia’s last century? what have these stories taught us;? how can we learn from Mongolia’s existence as a nation?

The history of Modern Mongolia reminds us that forgetting one’s own history, culture, and traditions is a threat to the nation. That is why, in this book, we attempted to reveal the facts of the bitter history that destroyed the values of the Mongolian nation’s existence: elimination of the succession of the golden lineages; ridicule of the intellectuals and scientists; and unconcern for the people. It is hoped that future generations of Mongolians will have their own view on these matters, and that they will be able to see Mongolia’s national interests as a priority. For it is those young people, who have learned from their own history, who will be honored as a member of a respected civilization.

The history of Mongolia that we publish here will contribute to the transformation of Mongolia’s social consciousness, history, literature and intellectual thought. Hopefully, Mongolian society in future will be one that favors democracy and justice, with an ideology that is free from foreign ideological influence.

The first and second parts of the book, “Renascent Bogd Khanate Mongolia” (1911 – 1919) and “Mongolia of Constitutional Monarchy” (1921-1924), respectively, were written by Sc.D., Professor O.Batsaikhan. Part three, first period “Mongolian People’s Republic (1924-1959), was written by Ph.D. Professor Z.Lonjid; part three, second period “Mongolian People’s Republic (1959-1990)” was written by Ph.D. Ch.Enkhbat. A special chapter on “Unforgettable lessons: the great purge and genocide in Mongolia” was written by Professor S.Baatar. Part four “Mongolia’s transition toward Democracy (from 1990-present)” was written by researcher and journalist S.Amarsanaa. Translated by Amar Batsaikhan (Part 1. 2), Dashdulam Budsuren, Naranchimeg Jukov (Part 3), Delgermaa Ganbat (Part 4).

The history of Modern Mongolia (1911-2017) project was funded by the ‘Mongolian Scientific and Research Institute for National Freedom’ and supported by the Konrad- Adenauer-Foundation.

We are forever grateful to the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung/Foundation’s Office of Mongolia for their support and would like to express our sincere appreciation to Dr. Daniel Schmucking and Dr. Peter Hefele, who were residing representatives at the time, as well as the current resident representative Johann C. Fuhrmann, and the project coordinator B.Dulguun.

PART ONE.

RENASCENT BOGDO KHANATE MONGOLIA (1911-1919)

Chapter One. POLITICAL SITUATION

1.1 Mongolia’s political environment and struggle to become a nation-state

In the early 20th century, Mongolia’s political situation and Mongolians were seen through the eyes of Moscow trade expeditions: “Mongols speak one language, use same one system of writing, one religion, one level of economy and cultural development. They have one common history and is under modern political conditions as well as the other countries. Occupying a large part of the northern part of Central Asia. The border of Mongolia lies in the west by the Khangai Mountains of Saylyugemsky, the Mongol Altai in the west, the Tanna Mountains and the Khamar Mount Hangai Mountains in the north, the Hinjang Mountains and the Great Wall of China in the south.” (Московская торговая экспедиция в Монголию, 1912: 167) This is a realistic reflection of the Mongols who lived “under the arms of others” for more than two hundred years.

Morozov of Russian expedition team states that Mongol population is relatively different, because there are with approximately 3 million people with population density of 0.7 people per square km (Moskovskaya, 1912: 218).

According to historical records, South Mongolia signed an agreement with the Dai Qing Empire in 1636. In the Manchu Khan’s decree: “By the power of the heavens I have ruled all nations and have a duty to care for you. My dear Bogd king, I am ordering this decree: (Полумордвинов 1912: 21)

...Spurious one, your brother was Tusheet Khan. You are the same as religion, and you had separate lands. You have worked together in every area of war.

You are rewarded with the title of King of the State because you took your efforts seriously and successfully invaded the three provinces, and three officers and 75 territories.

If my commands get violated in the ordinary time, or at the time of war, dukes, princes appointed by my decree shall be taken from their title and punished by the military tribunal. Other than that, any act of princes is not the basis for condemnation.

Prince’s post is inherited. If the Great Qinq dynasty changes, Mongolians will live up to their original legitimacy. For this she is awarded by heaven.”(Полумордвинов 1912: 21). This decree was issued and sent to the ruler of the right wing of Horchin prince Budach (who had title Zasagt precious of South Mongolia). Day the decree issued the 23rd of the first summer of Manchu’s Wise Bogd Khan’s first year is May 17, 1636. The record marks the year was the year Budach did got titled “Zasag tur, zasagt jun van” (Полумордвинов 1912: 21).

On May 5 of this year, the second representative of the Manchu royal palace, Hong Taiji (means Prince Hong) was exalted as Emperor, and his reign of governance was called “Chongde de” or “supreme wise” and dynasty was named “Dai Qing”. (Полумордвинов 1912: 21)

In other words, the events in 1636 and later in 1691 that led Khalkha Mongols to follow Manchu Empire were the historical empowerment of the Manchu emperor of the Aisingor family, and extended the Manchu empire with the Mongolian borders. The Manchu Khan’s decree mentioned above as well as the decree issued by Manchu Khan in 1691 for Khalkh Mongol in its essence, was a legal document that connects Inner Mongolia and Khalkha Mongols to Manchu, which is the first historical document of the jurisdiction of the Dai Qing Dynastic Empire. The strict rules governing the joining of the 1636 was undoubtedly implies the right of princes of Mongolia to the freedom of the Mongols to operate. Also this joining legal agreement in the body of decree specifies, since not only governing princes but every ruler participated and signed by supreme governers, each future decisions will be formulated just as same as the joining agreement. This was significant.

A right of the lords is: “If the Dai Qing dynasty changes, then it shall follow the original own law”. The Manchu Dynasty empowers the fate of the Mongolian rulers as the Qing dynasty. It was the evidence of the control of fate for princes only connected with Qing dynasty.

Whenever dynasty falls the contract defines freedom from any of the obligations of Inner and Khalkha Mongols as defined by the decree.

Khalkha Mongols joined the Manchu Qing Empire in 1691 as the alliance same as the South Mongolia. However, Eastern Mongols and Oirat Mongols defeated Manchu Qing Empire in the middle of the 1750s after many years of resistance. Since then, there has been a struggle to gain the independence of Mongols began all over the place.

Russian Empire and Mongolia

“If Manchu empire falls leading to escape their own Manzhouli, Government of China in Beijing would try to dominate. So before it happens, we should take Mongolia in as protectorate.” (Djon W.Stanton 1932: 214) noted N.Muraviev all the way back in 1853.

N.N.Muraviev is the diplomat who brought changes into inextricable fossil dynamic between Russian Empire and Manchu Qing dynasty. Works of his, especially, ‘Treaty of Aigun’ cooled down the heat of the relationship. Governor-General of the Far East N.N.Muraviev’s several diplomatic actions during 1850’s resulted the ‘Treaty of Aigun’ in 1858. (Муравьев-Амурский 1891: 56) This is a treaty signed between the two countries over a period of more than a century after the Treaty of Khyaga established in 1727. Now Russians consider this treaty historically victorious contract. No other treaty or contract that had impact on the dynamic had got signed in centuries between these empires. Only exchanging of diplomats or small trade pacts happened. After this ‘Treaty of Aigun’, between Russia and Qing ‘Treaty of Tientsin’ in 1858, ‘Convention of Beijing’ in 1860 got signed. According to the treaty, Russian Consul opened in Khuree in 1861 which made passing over the border of Mongolia much possible.

Muraviev, Governor-General of the Far East, sending representetives implied comradely relationship between him and representatives in Khuree. Because at the time, dynamic of two dynasties were on heat. Agent of Muraviev-Amusk, Despot-Zenowicz visited Khuree in 1854 and 1858 and the notes from the conversation between him and Mongolian governer is the most interesting. (Деспот-Зенович 2011: 163-167) In 1852, Taiping Rebellion was on the edge to escalate into revolution. Caused by the Manchu-Chinese’s war against England and France, the dynasty lost control of peripheral territories bit by bit. And Muraviev decided to take action into his hands.

He resolved to encourage the Mongols to separate from China, and Manchurians to do the same. And he supplied them with excellent reasons, and buoyed them up with hopes. Mongolia, he argued, is united, not with China, but with the reigning House there, and once it ceases to reign, the connection is at an end. And he promised each of these peoples help from Russia. These promises and negotiations were carried on through the intermediary of Despot Zenowicz, whose interviews with Amban were secret. In the secret conversations Despot-Zenowicz: “If the ruling dynasty falls on a disaster that Russia can not stop by the will of God, and Manchuria take over the Ming dynasty, Manchuria and Mongolss should not recognize themselves as a Chinese dynasty. Then we will help Manchuria and Mongolia.” “It will definitely happen unless there’s some god of disaster.” “From the historical point of view, there were three independent states of Manchuria, Mongols and China”. Additionally, N.Muraviev told through Despot, hoping “Mongols would become free as wild horse without rein running through field. (Dillon 1912: 56)

Mongols’ pride and hope rose for decades because of this speech.

In 1861, after the conversation, Russian Consul opened in Khuree. Since 1727, Russia had no external influence on Mongol, but afterwards, Russians started to compete with Chinese traders and Russian and Qing’s interests are in contact with Mongolia.

Mongolians of Buddhism

By the late-nineteenth century, almost every Mongolians started following buddhism which became the reason to lose own belligerent and wild behaviours. Yakov Shishmarev, a famous Russian diplomat, who spent some 50 years of his life in Mongolia, noted, when writing about Mongols in 1885: “Conflicts exist among the Mongols, particularly among Khalkhas and Tsahars. The khalkhas consider themselves a leading group among the many Mongolian tribes. They were submitted to a Manchu control in 1691. In case conditions are to be created for the Mongols to be united, the khalkhas are certain to lead the movement towards it. Many factors account for that. The most important one is that in Khalkha does reside the reincarnation of Avid Jebtsundamba who all Mongols and khalimags venerate”. (Донесение 1886: 154 – 160; Государственный архив Читинской области Ф.1 об, оп. 1, д.3292; Единархова 2001: 126)

The members of the Moscow expedition noted, when they wrote about the great reputation and influence of the Dalai Lama and the Bogd gegeen: “Since just one word of the Dalai Lama was capable of stirring up the entire Central Asia, the Chinese were very careful when choosing the Dalai Lama and the Bogd gegeen”. (Московская 1912: 228)

There were occasions in the early 20th century for the Mongolian issue to come to the attention of the Russia Emperor. Privy Counselor Lessar’s confidential telegram is still preserved in the Russian archives with the following notes made with a blue pencil by the Emperor himself: “I believe, Shishmarev’s trip to Khuree would be of great importance this time. He should be provided with necessary instructions” (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.78, с.1). A few days later, i.e., on 29 January 1905, Count I.I. Ignatev sent the following dispatch to his Emperor: “Mongolia is becoming a key in our policy towards Inner China, Tibet, Himalayan Mountains, India and Central Asia. The situation in Mongolia requires that we pay a special attention to an even development in this neighboring land linked to Russia through historical, political and economic interests. The issue of Mongolia is of a special importance for us despite the war with Japan. There should be no other option for Mongolia except becoming an autonomy and a buffer zone between Russia and China. She is certain to become in future a platform against China and a sphere of Russian interest” (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.78, с.3). Since the count’s dispatch included into the buffer zone all of Mongolia describing it as bordering with China on the south of Kukunor Lake (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.78, с.3), it is possible to view that the original Russian policy option towards Mongolia was not to divide Mongolia, but include all of it into the sphere of Russian influence. In addition, it was stated in the count’s dispatch that Russians’ objective should not be to divide Mongolia between China and Russia but to take a step to separate it from China (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.78, с.3). The count’s report might have helped to lay a basis for Russia’s policy on Mongolia in early 20th century. It was not incidental that the Emperor of Russia marked on the dispatch: ‘to be used in the report’ when it was submitted to him.

When V.N. Kokovtsev, Minister of Finance of Russia visited Harbin on 24-25 October 1909 to see the state of the railways there, I.Y. Korostovets (David Wolff 1999: 19-20), Envoy of Russia in Peking was also there”. The Finance Minister and Envoy then visited the Institute of Fareast in Harbin opened some 10 years earlier.

By 1900, Institute of Fareast, which was founded in October 21st or November 3rd 1899, had Korean-Chinese, Japanese-Chinese, Chinese-Mongolian, Chinese and Manchu language classes with 18 students studying there. Pozdneev taught Manchu and Mongolian languages till 1902. Tsybikov started teaching the Mongolian language since 1902. The Institute paid a significant attention to remote areas like Mongolia, Manchuria, Russian Fareast and Tibet in addition to China, Japan and Korea. Kiuner wanted to intensify the research on those areas. The graduates of the Institute set up in 1909 a Russian Association of Fareast Researchers.

During the Russo-Japanese war, Baranov traveled widely in and through Mongolia and sent a letter to Kokovtsev, Minister of Finance, dated 13 January 1907. He made in his letter a 10–point proposal on strengthening Russian interests in Mongolia. The proposals included setting up of Russian-Mongolian school in Harbin and publishing a newspaper in Russian and Chinese languages. (David Wolff 1999: 156)

But Baranov’s proposal was not supported. Year later in the summer of 1908, the Chinese started publishing a newspaper (Menghuabao) in the Mongolian. It was noted in its first issue that Japan and Russia were looking at Mongolia as “a tiger was looking at its game”. But the Russians had another idea. (David Wolff 1999: 163). The Russian started publishing a bi-monthly Mongol News in the Mongolian in the spring of 1909 in Harbin. Russians started to participate in issues related to Mongolia through Institute centred in Harbin.

Mongolian scholar R.Rupen noted: “The main reason for the Mongolian national movement of the 20th century was the change in the long and tolerant attitude of both Russia and the Manchu towards their Mongolian subjects” (Рупен 2000: 12). He continued to write: “The policy of the Imperial Russian Government which gradually became harsh since 1880, was most oppressive in 1902 – 1904. For one, Russians and Ukrains settled in Buriyatia, russified the region and tightened administrative control there. The Manchu changed in 1878 their previous policy to protect the Mongols from the Chinese. A new policy was developed fast and in a large scale during 1880 – 1890s and a decade from 1900 to 1910 saw a pinnacle of Sinification through steps such as allocating land plots in Mongolia to the Chinese. Even before 1880, Chinese farmers moved to Inner Mongolia beyond the Great Wall. Huc compared an advancing Chinese agriculture to “a snake crawling into the gobi desert””. (Рупен 2000: 12)

It had something to do with Russian policy that arrival of XIII Dalai lama coincided with Mongolian critical phase of time. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.78, с.5)

Dalai lama in mongolia and russian policy towards mongolia

The XIII Dalai lama left Tibet in 1904 and arrived in Mongolia to avoid the British aggression in Tibet and the negotiations imposed on him and the Tibetans. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.564, с.21) He might have calculated that the Russians would favourably recieve him in Mongolia and would support him on Tibet against Britain. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.78, с.5) The Russians, however, viewed the Dalai lama’s presence in Mongolia, as an opportunity to attract Mongolian and Chinese populations who profess Buddhism. Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.78, с.5)

Different interpretations and comments were provided on the arrival and stay of the Dalai lama in Mongolia and his relations with the eighth Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu. The information sources preserved in the Russian archives might help clarify them. In one of the Russian sources it was noted: “conflicts start to break out between the Khutuktu of Khuree and the Dalai lama. If the Dalai lama continues to stay in Mongolia, the Khutuktu is likely to move to the Erdene Zuu Monastery in the Orkhon river basin”.(Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.78, с.5 об) It is difficult to say if the Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu was indeed thinking of moving to the Erdene Zuu Monastery. It is, however, probable that he did not like the influence which the Dalai lama began to have after his arrival in Mongolia and which led to the reduction of his own. The Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu could also have been concerned that the Dalai lama might act in an inappropriate and untimely manner vis-a-vis the movement for Mongolia’s national independence that he was contemplating about.

Russian Scholar P.K.Kozlov noted (Козлов 2004: 105) in his diaries that he met with the Dalai lama more than once while he was residing in the Khuree. It was also noted that the Manchus and Chinese in Khuree became suspecious of the close relationship between the Dalai lama and P. Kozlov.

There are original stories passed on from mouth to mouth on the meeting between the Bogdo gegeen and the Dalai Lama. (Жамсранжав1998: 75)

The Dalai lama stayed in Khuree for a while and went to the Wan Khuree in the summer of 1905. Although the Dalai Lama was enjoying the support of many Mongolian worshippers, he had to leave because of a number of factors, including the Khutuktu’s cold attitude towards him, Russian consul’s avoidance to see him in person and Manchu Amban’s persecution. The Dalai lama told the Russian consul before he left Khuree: ‘The Khutuktu sent monetary presents to the Manchu Emperor to persuade him not to receive the Dalai lama and he was not accepting Khutuktu’s offer to give a reception in his honour. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.564, с.80-96)

According to the report of the Russian consul, (Россия и Тибет 2005: 26)the Khutuktu of Khuree did not meet with the Dalai lama in order to avoid diminishing his high reputation among the Mongols. But the words of mouth among the Mongols had it that the Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu met with Dalai lama more than once under the cover of night to avoid the persecution of he Manchu authorities. According to Russian scholar P. Kozlov, the Dalai lama was very frank when he met with him, saying: “the Khutuktu not only did not meet him and pay a visit to him in his residence in Khuree. Moreover, he allowed his seat to be removed from the monastery”(Козлов 2004: 106). He also noted (Козлов 2004: 106) that the Khutuktu of Khuree did not like the presence of the head of the Tibetan religion in Khuree because of the alleged Peking attitude. The Dalai lama did not like the Khutuktu either”.

The Dalai lama attempted, while he was in the Wang Khuree, to carry out political activities and, in particular establish direct contacts with Russia. When the Russian Government started negotiating on Tibet in 1906 with the British Government, it was considered appropriate for the Dalai lama to go from Mongolia to Kumbum, which he did on 26 August 1906.(Россия и Тибет 2005: 28)

Russians, then, wrote, “Khalkha princes and nobles follow Khutuktu on political and other important issues. For them Khutuktu’s views and words are sacred. It is important to have an influence on him. Caution, however, should be taken when placing a hope in Khutuktu.”(Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.78, с.5 об). The remark, as I see it, alerted to the importance of treating Khutuktu correctly, without denying the possibility of placing a hope in him.

Careful analysis of the content of the information and documents of that time shows that the Russians attached a particular importance to influencing the Mongols, using the doctrines of their religion, Buddhism. At the same time they paid much attention to attracting hereditary nobles popular among the masses and favorably impacting on them. It was because of this, perhapse, that they were very careful when treating the Dalai lama.

It was not only the Mongols who were concerned about the new policy course being enforced by the Manchu Government. The Russians did not favor the policy either. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.78, с.22) Lyuba proposed consequently on 16 June 1905 that the Khuree consular district be reduced and that an additional Russian consulate be created in Uliastai. Consequently Russian consular offices were established in Uliastai, Khovdo and Shar Soum of Khovdo.

The members of the Moscow Trade Expedition, who had taken a trip to and in Mongolia during the said period wrote: “Civilization’s advances did not reach here (Mongolia) untill recently. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that it is only now, before our eyes, that the centuries-old way of their life inherited from generation to generation is beginning or is about to change”. (Московская 1912: 68)

G. Osokin wrote about the Mongolia of early 20th century: “We have certain important trade and political interests in Mongolia. We, therefore, should focus our attention on this country in crisis. Mongolia borders on our possessions in Asia along thousands of miles of land. What is happening in that country and who is establishing themselves there, should be our concern. It may be natural for Mongolia to be in economic relationship with us and be our market in terms of both natural environment and geographical location”. (Осокин 1906: 28)

Baranov Aleksei Mikhailovich (who undertook several survey trips in Mongolia in 1905 - 1906), a Russian military specialist on Mongolia, who served in Russian military intelligence, wrote: “Mongolia enjoys a status of semi-independent nation. It is not occupied by China (Manchu Qing State — O.B.), but is associated with it. The Chinese intention and desire to unite Mongolia to themselves, led to the elimination of the Mongolian self-rule and gave rise to the issue of Mongolia”. D.P.Pershin, (Баранов 1907: 6) Official for Special Matters, Office of the Governor-General of Irkutsk, wrote in the newspaper “Siberia”: “Russia needs an independent Mongolia as a buffer-state. Russia will do a lot to strengthen this buffer”. (Першин 1910: 4)

All the words, above-mentioned, from Russian government, business and military representatives are on the one hand shows the Russian policy towards Mongolia, while being an indication of passion to become independent nation from Mongolian side. And it preceded critical state of nation that soon to be defined.

The History of Modern Mongolia (1911-2017) UB., Hard cover (Хатуу хавтастай) - 40.000 tugrug (төгрөг)

Prof. Batsaikhan Ookhnoi Phone: +976 11 362281 Fax: +976 11 322613 E-mail: bagi112005(at)gmail.com

MONGOL’S STRUGGLE AGAINST MANCHU POLICIES

The irreversible demise of the Manchu empire provided an impetus to the break out of the national revolution in Mongolia. But the main causes of the Mongolian National Revolution of 1911 were several: Mongols had originally existed independently; the struggle for their national independence started following their submission to the Manchu domination, to be exact, after the Manchu attempted to control and restrict Mongols’ freedom and conducted a policy of assimilating Mongolia. As early as 1899 or the 25th year of Guangxu, the chuulgan dargas, commanders, beice da Hebei, the eredene shanzodba of Khuree of the four Khalkha aimaks petitioned jointly the Ikh Jurgan(Lifanbu) to not let extraction of gold on the territory of Mongolia.(Петухов 1939: 85) Although a protest was lodged in and through this document against the permit given to Russians to extract gold, through the remark that ‘it had been the common conviction since ancient times that gold should not be sought and extracted for profits in violation of prohibitions’ (Петухов 1939: 85-86), an idea was clearly expressed that whoever, be it a Russian or Chinese, should not dig for gold and that an extraction of gold is contrary to the Mongol tradition.

It was a time when the aspiration of the Mongols to get rid of the Manchu domination and attain their freedom was gaining a momentum in Mongolia. Russian merchant A.Burdukov who lived over 30 years in western frontier region of Mongolia wrote: “The northern Khan Khoukhou mountain valley was full of talks about the events that would wake up the Mongolian people of their centuries of sleep and would bring them freedom and right to participate in the creation of mankind’s history” (1969: 28). The dispatch sent in January 1908 by the French Embassy in Peking to its MFA reads: “The lamaist religion has undoubtedly suppressed the warrior spirit of the Mongols. But it can also help revive it. Although the Mongols were discouraged and lost their power, they remain loyal, brave and concerned about their reputation” (Франц 2006: 153).

Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, being unable to go along and being often in conflict with the Manchu amban, secretely collected and kept weapons in his palace. He considered that a lot of weapons would be needed in the organization of national struggle. Nevertheless, the Manchu emissary became suspicious and found it out in 1908”. (Жамсран 1996: 38) In the 34th year of the reign of the Manchu Emperor Guangxu (1908), the Tusheet khan and Setsen khan aimaks as well as the shabi petitioned jointly to the Minister in Khuree to make a “point of protest over the difficulties of procuring for for heating by the officers and cavaliers stationed in Khuree as ordered by the Minister”. (Петухов 1939: 87)

Yu. Kushelev, a Russian military officer, who, at the instruction of the General Department of the Russian Armed Forces’ General Staff, traveled though Mongolia from April to October 1911, wrote: “The influential lamas of Khuree held a meeting in late June 1905. The meeting decided to oppose to the new policy of China (Manchu Qing State —O.B.) and send a delegation to Russia to seek assistance in this undertaking”. (Кушелев 1912: 2) He noticed that South East Mongolia was more attached to China while Outer Mongolia was more independent and South West Mongolia had relations with Russia. (Кушелев 1912: 78)

As for Korostovets himself, his connection to Mongolia dated well before the Mongol — Russian Agreement of 1912 that we know. In 1907, after the Russo — Japanese War, he gave secret instructions to Hitrovo “to review the situation in China and Mongolia and promote friendship between Russia and Mongolia” (Дэндэв 2003: 6). This was mentioned in detail in the petition that Dambadugar, Tsydipov and Inet, the Buriates of Altanbulag town, Selenge aimak, submitted to the Presidium of the State Small Hural in 1933, where they reported on the historical activities that Inner and Outer Mongols had initiated and undertaken since 1904 to break away from the Manchu and create their independent state. It was noted there that I. Korotovets who was a Minister in the Russian Legation in Peking gave secret instructions to Hitrovo, and they acted as interpreters and took trips, to implement the instructions, to Barga, Over (Southern) khoshuns and areas of Khalkha Mongolia (Дэндэв 2003: 6). It was also mentioned there: “Russia found out that discussions had taken place (among the Chinese) circa 1907 on sending the Chinese to Barga and Khalkha Mongolia’s northern border areas manned by Mongol frontier guards and having them settled there to grow wheats and cereals. Since it would be difficult for both Mongolia and Russia if there would be no Mongolia to maintain relationship, Zasagt wang, officer Hitrovo and my brother Tsevegdorji discussed the possibility of making Barga and Inner and Khalkha Mongolia self-governed and conveyed their ideas to Korostovets who was then a Minister in Peking. Korostovets shared their views but was cautious limiting his support for only Khalkha Mongolia for Barga and Inner Mongolia had many Chinese farmers and it would be difficult for them to seek independence. (Дэндэв 2003: 6-8) It was after this that Almas-Ochir, ex-governor of Harchin Wang khoshun was sent to Khuree. He reported to Bogdo who endorsed the views expressed and it was decided that an information would be exchanged between them as between a lama and a disciple. (Дэндэв 2003: 6-8)

A. Kornakova wrote: “I learned from conversations with the Mongols that Bogdo Gegeen and other influential princes and lamas have regularly met and consulted during the course of the last two years”. (Корнакова 1912: 18) Consul Ya. Shishmarev wrote after the Bat- orshil Naadam of 1908: “Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu does not allow influential princes of Mongolia to return to their regions. Without his consent and blessing, no khan, no influential lama can now leave. He has now become a leader of the Mongolian side”. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.17) He added that Sain noyon had become the person closest to Bogdo.

Mongolian princes and nobles often discussed, in the presence of Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, about the present situation of and perspectives for Mongolia. But Bogdo and princes, at that time, considered a special matter for the Manchu authorities, namely the demand of the Manchu Ministry of Finance put through their amban in Khuree that the Chairman of the Mongolian Chuulgan and hoshun governors give them a clear response to their following questions: (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.18)

a) WhyitisconsideredimpossibletoletintoMongolia,avastterritorywith little population, Chinese citizens and let them engage in farming,

b) What, under the present conditions, prevents a construction of railway between Khaalgan and Khuree and what justifications are there,

c) IftheChinesesettlementandtheirengagementinfarmingaswellasthe construction of rail way and auto vehicle roads are to negatively affect Mongolia’s nomads and animal husbandry, why an engagement in mining is also considedered to be negative.

Jebtsundamba Khutuktu and other Mongolian princes were demanded by the Government of the Manchu Emperor to respond to the above questions in no ambigious terms. Therefore, they had to thouroughly consider the questions and provide proper answers to them.

Khutuktu and princes, after thorough consideration of the questions, defended their previous position on opposing to the Chinese settlement in Mongolia and their engagement in farming and expressed, their conviction that mining would also entail many consequences for pastoral livestock breeding which required moving to mountains during winter.(Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.18) The meeting of the Mongolian princes made all the participants to realize that Mongols’ life was becoming precarious and that it required a lot of attention and efforts to protect it.

One of the notes that the Russian Consul Shishmarev made in early 1910 in his diaries reads: ‘The relationship between the Khutuktu and Sandowa amban in Khuree is becoming worse over the lamas’ incident. Sandowa reported to Peking that the Khutuktu and the Shanzodba are not implementing the Peking instruction to dismiss the Secretary General and Da Lama. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.33)

The Russian Consul’s dispatch of 18 May 1911, informed of the Chinese Government decision taken early 1911 on replacing the Mongolian border guards, who served under the supervision of Chinese amban in Khuree, by Chinese troops (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.566, с.10) and noted that they started implementing their military reforms. Jebtsundamba Khutuktu and Mongolian princes were particularly opposed to this miltary reform being carried out in Mongolia by the Manchu authorities.

LAMAS’ RIOT IN KHUREE

The incident started on 26 March 1910 when three Mongolian intoxicated lamas entered into an argument and fight with salespersons of a Chinese shop. When Chinese troops acting for police arrested the lamas and attempted to take them to a police station, many Mongols who happened to be there on the street, attacked them and were said to have destroyed the Chinese company. The Manchu amban Sandowa hurried to the place of the incident to regulate it as soon as he got the news. Many Mongols who were hardly controlling their anger met the amban with shouts and threw stones at him when he was at some distance from his carriage. Sandowa could not do anything but go back to his carriage and drove away. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.34) Manchu amban Sandowa, having been hurt during the riots, made great efforts to identify and arrest the main culprit of the event, arresting and imprisoning many lamas involved in the riots. He came, ultimately, to the conclusion that the main culprit was Khutuktu’s assistant, his Secretary General. Khutuktu, however, did not let Sandowa arrest the Secretary General. On the contrary, he was said to have hidden him in his palace. On the account of the Sandowa report, Peking instructed the Khutuktu to sack Secretary General Badamdorj and Da lama Tserenchimed from their posts. But he did not carry out the instruction. On the contrary, he wrote and sent a report to Peking in May 1910, wherein he charged Sandowa of attending the riot and fiercely defended the Secretary General who was his closest person. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.54) Since then the strained relations between the Khutuktu of the Khuree and the Manchu amban got worse and turned into deep animosity. That being the case, Jebtsundamba khutuktu sent several letters to the Manchu Emperor to have Sandowa replaced and even sought assistance from the Russia Consul on that matter. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.55) Lavdovskii, Russian Consul in Khuree informed Korostovets, Minister in Peking through his dispatch of 12 March 1911: “The Gegeen refused to mark the Lunar New Year on the same day with the Manchu and Chinese and instructed the Mongols to celebrate it a day later. Khutuktu did not receive Sandowa amban when the latter came to pay a respect to him on the occasion of the Lunar New Year. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.90)

I believe the above incidents showed that the Khutuktu of Khuree existed and acted independently from the Manchu amban. As for the riot, it was not a mere law - and - order incident involving few lamas, but an event with serious political implications. It let the Manchu amban see for himself how the tense situation in Mongolia was close and ready to turn into an all-out movement of protest.

Morozov’s expedition team also wrote in their travel notes: “For Mongolia the Bogdo gegeen is a holy khuvilgaan of the first order.” which was not far from the truth. Reputation of his among his people increased regarding as the Khuvilgaan of Eighth Reincarnation and as a person.

The Bogd gegeen was semi-independent in his relations with the Chinese. He did not pay visit to Beijing as was the case with his previous incarnations. The Chinese could not do anything to have him visit.

The Bogd gegeen took a negative attitude when the Dalai Lama arrived in Mongolia. The Dalai Lama could not find any means to ameliorate his attitude towards him. This led to the decrease of the Dalai Lama’s reputation among the Mongols and to the increase of the Bogdo’s fame.

Increasing resort to the Bogdo gegeen for consultations by princes who were aware of the difficult situation in Mongolia and who were disappointed with Manchu authorities and the position of the Bogdo gegeen as attracting the princes made the Bogdo gegeen a political head of the Mongolian nation.

But the main instrument through which the Bogdo gegeen could influence the people were lamas. All the lamas of Mongolia were governed by the Bogdo gegeen. Any young lama of any monastery in Mongolia could not get status of a most low ranking lama without being blessed by the Bogdo gegeen. Therefore, all lamas were dependent on Khuree.

Morozov noted that about two hundred thousand lamas and laymen come to the Bogdo court to pray before him”. (Московская1912: 227)

It was a law for all monasteries and the population of Mongolia to worship the Bogdo. In this situation, all lamas, in addition to his disciples, were turning into his subjects. Since the influence of lamas among the people was strong, the influence of the Bogdo gegeen was growing fast among the population. (Московская 1912: 177-178)

In the middle month of 1910, the superiors and princes of the four aimaks had met in Khuree and convened princes’ meeting in accordance with the order made by the Bogdo the previous year to consider a case “for the need to establish an independent Mongolian state” (Дилов1991: 7) – a case approved by the seals of the princes of the four aimaks. The meeting was attended by four princes, representatives from each aimak and the shabi. When the princes’ meeting was considering the issue, Sandowa Amban in Khuree became suspicious and the meeting was adjourned. But the consideration of the matter continued in the summer of 1911 under the pretext of offering danshig services dedicated to the Bogdo.

The khans, princes, officials, khutuktus and khuvilgaans of the four Khalkha aimaks met in the summer of 1911 at the office of Khuree’s Erdene Shanzodba under the pretext of holding, by Bogdo‘s decree, danshig services by many aimaks and shabi and discussed how to oppose to the ‘new Manchu policy course’ and restore Mongolia’s independence. Since it was difficult to reach a consensus decision by many participants who held different views and who were not free from the persecution of the Manchu amban, a group of people, including princes and lamas headed by the four Khalkha khans, who were opposed to the new policy course of the Manchu Government and who believed that it was high time for Mongolia to become independent for the sake of her national identity, religion, state and land, held separate consultations in secret, meeting in a gher set up in the woods at the back of the Bogdo maintain.

It was decided by the princes’ secret meeting to “send a special deputation to Great Russia, the northern neighbor, to kindly explain Mongolia’s situation and seek an assistance for the foundation of the Qing Government became shaky and it became impossible (for Mongolia) to bear foreign officials’ and ministers’ oppression and exploitation and their complete disregard towards Mongols’ interests, although it was necessary to get independent and protect Mongolia’s religion and land, it was very difficult to do so without foreign assistance” and to “appoint chin wang Khanddorj, da lama Tserenchimed and official Khaisan as the deputation”(Магсаржав 1994: 8). V.Lyuba, Russian Consul in Khuree noted in his dispatch of 22 January 1912 that sain noyon and Tushee gung, chuulgan darga of Tusheet khan aimak were closest to Bogdo and they along with Shanzodba assistant, junior da lama Tserenchimed played a special role in the decision to send the Mongolian deputation to Russia and in changing the situation in Mongolia. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.566, с.38) The Russian Consul also included Kharchin official Khaisan in the list of the persons who made a special contribution to the cause of the revolution. He noted that gung Khaisan had promoted the idea of Mongolia’s independence and appealed to all Mongolian nationalities to unite, for many years and wherever he had gone to, be it Harbin, Kyakhta or Mongolia.

M. Tornovskii noted, in this connection: “Bogdo the Venerable, could successfully hold, over the heads of their enemies, businesslike negotiations with the Imperial Russian Government to get an assistance for Mongolia. He managed to get the support of the princes and noblemen who believed in the possibility of obtaining their freedom from the Chinese with the Russian assistance.” He wrote that princes, noblemen and lamas met in Khuree in June 1911 under the leadership of Bogdo the Venerable. (Торновский 2004: 182)

The report of staff captain Makushek on the visit of Mongolian Delegation to Russia

Chin wang Khanddorj, decsendant from the Chinggis Khaan lineage, ruling prince of Tusheet khan aimak, lieuthenant general of the Chinese army. Wise, (Chinese) educated. Weak and irresolute. Therefore he have been appointed as a Khalkha Mongolian (86 khoshuns’) plenipotentiary representative in the Advisory Chamber in Peking. Has always been pro-Russian and has always longed for independence from China.

Khaisan, Major General of the Chinese Army. Indefatigably hard working, lectures on the right of Mongolia. Has worked last five years for the resolution of the Mongolian issue in favor of Russia. He is the main person who encourages the Bogdo Gegeen and has been instrumental in strengthening the position of the Mongolian princes to seek Russian protectorate. Urges Mongolia to rise up, considering the present a most opprtune time. Believes that Mongolia must revolt with clandestine Russian support and weapons.

Da lama Tserenchimed. (Advisor to the Bogdo Gegeen). Strongly pro-Russian, wise, cautious, devout buddhist, (Tibetan and Mongolian) educated. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.162-163)

The above description was undersigned by Staff captain Makushek to certify its authenticity.

The compostion of the Mongolian delegation shows clearly that its members were all educated persons and that they were pro-russian and supported the struggle for Mongolia’s independence. The word ‘Chinese’ is retained as was written in the original although it should have been written ‘Manchu’. The word ‘Chinese’ was then used in most of the Russian documents.

The Mongolian delegation, having presented their case, was waiting for a formal response. Soon the following response was given. The Russian Government advised: “... the preparation of the Mongols is not sufficient...Mongols’ aspiration to secede from China might not be materealized now...Russia truly wants the situation in neighboring Khalkha to be peaceful and favorable. Russia would support Mongolia to rule herself, ensure the stability of her internal situation and oppose to the Chinese penetration into Mongolia’s administration and military. A Russian Envoy in Peking would take an action so that the Chinese Government would not persecute the Mongolian delegation to Russia and those who sent them. The Russian Consulate in Khuree is being strengthened by two hundred soldiers and manchine guns”. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.110)

Meanwhile Manchu amban Sandowa ordered to arrest wang Khand and others and announced rewards to those who would help arrest them. He also had the Bogdo palace beseaged and ordered not to let anybody from the Russian consulate in and forbade Mongolian princes to meet with anybody from the Russian consulate. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.199)

On 3 August, i.e., two days after the Mongolian delegation reached the capital city of Russia and met with the representatives of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Council of Ministers of Russia held a special meeting on the Mongolian issue. The meeting defined the policy course that Russia was to adhere to on Mongolia. A secret telegram sent by Russian consul Lavdovskii a month later informed that 200 kossack troops and four officers, with two machine guns, arrived at Khuree in the evening of 2 August. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.204) It shows that the the protection of the Russian Consulate in Khuree was strengthened.

The first to arrive at Khuree was Da lama Tserenchimed. He came disguised as a Russian military physician. ((Ширэндэв 1978: 372)

Gung Khaisan informed Kotwicz through his letter of 24 November 1911 that Bogdo was presented with petitions to the effect that activities be promptly undertaken for the great cause and that the present opportunity should not be missed.

The composition of the General Provisional Administrative Office for the Affairs of Khalkha Khuree included Tushee gung Chagdarjav and Jun wang Gombosuren as its head and associate head and commander chinwang Khanddorj, assosciate commander and hebei beis Gombosuren, wang Tsedensonom, gung Namsrai and Da lama Tserenchimed as provisional counsellors and executives. Also Tushee gung was appointed as the head of the Provisional Government. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.282) The establishment of the Provisional Administrative Office was necessitated by the need to declare Mongolia’s independence.

So important first objective of the Provisional Government was to restore and declare Mongolia’s independence, which it did on 1 December 1911 by and through publishing a Proclamation declaring the end of the years of Manchu rule and the establishment of the Mongols’ independence. A flag with a soyombo letter, a symbol of national liberation and independence, thus, began to fly in Ikh Khuree. (Сандаг 1971: 252)

Russian consul Lavdovskii reported about the declaration in his secret telegram sent on 18 November 1911: “This morning princes issued a proclamation. It declared Khalkha an autonomy” (Международные 1938: 178). Another Russian source, namely Avetisov, lieuthenant colonel of Russian Military Staff, Military commander of the Consulate in Khuree, wrote in his telegram of 1 9 November: “Yesterday Bogdo Gegeen declared Mongolia’s independence”. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.268). Autonomy in this context meaning the independence of Mongolia. Everything appeared to proceed according to his intention and under his leadership. It is possible to view that Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu fully controlled and directed this courageous step and all political activities taken place in Mongolia since the summer of 1911, organizing them skillfully and in complete secrecy.

According to the memoirs of Ataman Semenov (Semenov - Georgyi Mihailovich Semenov (1890-1946) was an organizer and leader of the movement of the White Guards of Baikal vicinity. Lieutenant general and ataman of the Cossack detachment of Baikal vicinity.) Semenov was in Khuree when the national revolution of 1911 broke out in Mongolia and ‘took part in writing the history of Great Chinggis Khaan’s state’. According to Semenov, he escorted Sandowa amban until the latter crossed Mongolia’s northern borders. He wrote: “I and my Cossack company were enthrusted by our Consul to protect the Chinese amban in Khuree.” (Атаман Семенов 2002: 18-21)

The above telegrams, notes and diaries show Jebtsundamba Khutuktu and the Provisional Government acted on expelling the Manchu amban and declared Mongolia’s independence without the participation of Russia. The activities carried out were not only a result of brave decisions taken in a timely manner. They were historical events that left a vivid imprint in Mongolia’s future.

Sandowa made special efforts to implement the new policy course and paid a particular attention to the Manchu Government. Special effort Sandowa made to implement the new policy course made the Mongols more apprehensive and compelling them to seek the cause of independence for themselves.

The Mongols composed a song when Sandowa amban was expelled from Mongolia. It was included by L. Dughersuren in his book on Ulaanbaatar’s History. The lyrics of the song reads:

“The stinky lanterns that glowed

Every evening, are burnt out,

Where is gone the notorous amban

Who commanded the masses” (Дүгэрсүрэн 1956: 46)

In his interview given to the employee of a Harbin newspaper ‘New life’, Sandowa said: “I was given an ultimatum that I and my officials leave Khuree within three days. After leaflets were posted on streets, announcing that the privileges and immunities of the amban and Chinese officials were not to be recognized after the said term.” (Харбинская газета “Новая жизнь” 13 Декабря, 1911 года)

Since the Sandowa amban of Manchu-Chinese was expelled, Provisional Government took the state power by the decree of Bogd Gegeen. The following statement was issued on the 13th day of the first winter month of the year of pig or winter of 1911: “Since the Provisional Administrative Office for Khuree Affairs had decided to establish (Mongolia) as an independent state and expelled Sandowa amban, we, six persons have now taken over his responsibilities”. (Сандаг 1971: 101)

The Provisional Administrative Office anounced the date for holding a great national ceremony for elevating Bogdo Gegeen Jebtsundamba to the throne as the Emperor of the Mongolian nation as an establishment of the institutions of the Mongolian state and government. The news were disseminated throughout Mongolia. The Imperial Russian consul in Khuree was also formally notified. (Үндэсний төв архив ф.4, д.1, х.н.136)

The Provisional Government of Mongolia organized a series of important activities such as expelling the Manchu amban in Khuree, proclaiming Mongolia’s independence, setting up state funds and enthroning the nation’s khaan who was an expression of her independence.

It was noted by Dilov khutuktu: “Eighty thousand lan mongu in total with contribution of twenty thousand lan mongu from each aimak were collected for setting up a basis for the state finance and the Bogd khaan had contributed from his fund two thousand four hundred ingots of silver, each worth of 120 thousand lan mongu to the cause of restoration by Mongolia of her newly established statehood, the declaration of her independence and conduct of state affairs”. (Дилов хутагт 1991: 8)

The Provisional Administrative Office for the Affairs of Khalkha Khuree issued on 1 December 1911 a proclamation on the restoration of the Mongolian national state. It was decided by the proclamation to terminate the use of the Manchu calendar with the reign title of Emperor Xuantong and use, instead, the Mongolian calendar of a twelve year cycle with the year then being that of white female pig. (Үндэсний төв архив Х.1, д.1, х.н.32) An another document sent on the same day instructed ‘each of the Tusheet khan and Setsen khan aimaks to mobilize 1500 troops and each of the 47 guard posts to provide 1 commander and 9 soldiers”. It also instructed “the Zasagt khan and Sain noyon khan aimaks to have their troops ready at the offices of their commanders and liberate Kobdo and Uliastai after princes and officials from Khuree arrived at the offices”. (Үндэсний төв архив Х.1, д.1, х.н.32) The Sain noyon khoshun of the Sain noyon khan aimag presented 1320 lan mongu in 1912 to express its felicitation on the occasion Bogdo’s enthronement. This khoshun contribute 5000 lan mongu to military uses and 2000 lan mongu to the repair of the Bogdo’s palace in 1915.

TUSHEE GUNG CHAGDARJAV

Chagdarjav who worked as a khoshun zasag and Chuulgan darga of Tusheet khan aimak, took a prominant part in the cause of the Mongolian National Revolution of 1911 and was one of those who initiated and led the national revolution. (Монгол Улсын шастир 1997: 18-20) He worked as the first head of the Provisional Administrative Office for the Affairs of Khalkha Khuree formally established on 30 November 1911. Tushee gung was the Chief Minister of Finance. He took part in the Kyakhta negotiations of 1915 as a plenipotentiary representative of the Government of Mongolia. When the Kyakhta negotiations ended on 7 June 1915, he returned to Khuree and a month or so later passed away under suspicious circumstances.

JUNWANG GOMBOSUREN

Erdene dalai wang Gombosuren Galsannamjil was one of the six persons who seized the state power from the Manchu authorities. He was born in the territory of Erdenetsagaan soum of present day Sukhbaatar aimak. He inherited in 1900 the post and title of a khoshun zasag and in 1910 became an assistant commander of his aimak. When Ochirdara Bogdo gegeen was enthroned in 1911 as the Emperor of Mongolia and distributed favors and presents, he was appointed Deputy Prime Minister, Minister, chief Minister for Military Affairs and a commander of Setsen khan aimak troops. Монгол Улсын шастир 1997: 70-72) He passed away in the spring of 1914. It was noted in the archival source that “he died of a disease”. (Үндэсний төв архив Ф.А47, д.1, х.н.6, 1 дэх тал)

GUNG NAMSRAI

He was one of the six persons who seized state power from the Manchu authorities. He was an eldest son of zasag noyon Mijiddorj of Tusheet khan aimak’s Erdene zasag khoshun. Worked as Chief Minister of Justice. (Монгол Улсын шастир 1997: 21-24) Chinwang Namsrai was conferred on 30 July 1919 with a hereditary rank of chinwang for the second time for his five-year continuous faultless service in the Ministry of Justice.

DA LAMA TSERENCHIMED

He was born in 1872 in the family of a commoner belonging to Bogdo’s eclesiastical es- tate. He joined Bogdo’s secretariat (Shanzodba’s Ministry) as an assistant clerk and later on, promoted to a reception clerk of the Shanzodba’s Ministry. Before becoming a Da lama he worked as a clerk for Da lama. It was noted in one of the sources that he became Ikh Khuree Shanzodba in early 1909s. He befriended with harchin scholar Khaisan for several years and endeavored to make Mongolia an independent state together.

Da lama Tserenchimed is one of the six persons who seized state power from the Manchu authorities and established the Provisional Government of Mongolia. Bogdo, as the Emperor of Mongolia, conferred him Vice Prime Minister and Chief Minister of Interior. Since the Ministry of Interior led other Ministries, da lama Tserenchimed was the Chief Minister of the Government of Mongolia. (Үндэсний төв архив Ф.А3, д.1, х.н.23)

Dilov khutuktu noted: “Sain noyon khan and da lama Tserenchimed, Chief Minister of Interior were the two main figures who made genuine efforts in the cause of the Mongolian state at this time (meant the immediate post – 1911 period – O.B) (Дилов хутагт 1991: 14)

In his letter of 18 March 1912 to V.Kotwicz,F. Moskvitin wrote: “There are no knowledgeable people in Mongolia. Da lama is very stubborn. He is easily involved in the trivial. But it should be recognized that he is the best authority to be found in Mongolia.” (Котвичийн 1972: 178)

Korostovets noted that Da lama Tserenchimed took a rather tough position in the beginning of the Russo - Mongolian negotiations which led to the conclusion of 3 November 1912 agreement.

I.Korostovets singled out da lama Tserenchimed who was the most energetic from among the Mongolian delegates and noted: “The Da lama demanded, based on the Blunchleg theory of international law, that the result of their agreement reflect ‘all the territory, including that of Inner Mongolia where the Mongols live, should be under the authority of the Khutuktu.’ (Коростовец 2010: 56) And he continued, “The Da lama appears to be a most active and wise person out of the members of the Government here, or nomads of a primitive community who conferred themselves an honourable title “Minister”. He is our main, wise and cautious competitor. He is an honest and experienced person who is not corrupt and does not trust in others”. (Коростовец 2010: 26) I believe, his conclusion is quite accurate.

The Russian newspaper “Novoe Vremya” wrote describing Da lama Tserenchimed: “He is an iron-willed and very courageous person with inborn talents. He is also expeditious and sensible, but more nationalist than pro-Russian”. (Новое время, 8 Сентября 1912 года)

In the fourth year of the ‘Elevated by Many’ or 1914, the Da lama, Chief Minister of Interior passed away when he was traveling in two westernmost aimaks along with beil Sodnomdorj, Vice Minister for Justice in order to settle the affairs of the Uuld and Torgut people who were distressed because of Dambiijantsan’s activities.

Daily newspaper Siberia published an article entitled “Da Lama” in its 28 June 1914 edition. In this article, it was noted that more should be told about him for this loyal son of the steppe shouldered enormous social and political responsibilities.

ERDENE WANG KHANDDORJ

Khanddorj was one of the statesmen who played a leading role in the Mongolian National Revolution. As decided by the secret meeting happened in the Bogdo mountain, Khanddorj, Da lama Tserenchimed and gung Khaisan were sent to Russia to seek an assistance.

In 1911, Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu conferred him as Vice Prime Minister and Chief Minister for Foreign Affairs. Khanddorj paid, as the Minister for Foreign Affairs of Mongolia, the first high-level visit of the new Mongolian state to the Russian Empire in late 1912 and early 1913. It was noted in an archival source that he fell from a horse and died (Үндэсний төв архив Ф.А73, д.1, х.н.139, 10 дахь тал) on the 7th day of the first spring month of 1915 (Болдбаатар 1994. Дэндэв 2006: 67).

GUNG KHAISAN

Gung Khaisan was born circa 1862-1863 in the khoshun of Kharchin wang Gunsennorov of Inner Mongolia’s Zost chuulgan. He led a rebellian against the Chinese migrants who immigrated into Inner Mongolia. “Meiren and learned official Khaisan, governor of Kharchin wang Gunsennorov’s khoshun and Ochir Almas arrived at Khuree around 1907, met with Mongolian lamas and princes who were local authorities, condemned the cruel and tyranical policies pursued by the Chin state in their territories and discussed on how all Mongols would unite and become powerful and strong” (Магсаржав 1994: 6) He was one of the delegates who secretly went in the summer of 1911 to Russia to seek an assistance. He was rewarded by the decree of Bogdo khaan with the rank of Tushee gung for an active part in the liberation of Kobdo while he was appointed and worked in 1912 as counsellor to Jalkhanz Khutuktu Damdinbazar, Plenipotentiary Minister for Handling the Affairs of Westernmost Region. When troops were sent by the Mongolian Government in 1913 to liberate Inner Mongolia, he was appointed and led the second group of the troops who moved into Inner Mongolia in five directions. When Inner Mongolian princes returned after the conclusion of the tripartite Kyakhta agreement of 1915 between China, Russia and Mongolia, Khaisan joined those returning. He passed away in 1917 in his native land.

Russian Consul General V.Lyuba in Khuree included gung Khaisan in the circles of Bogdo khaan’s confidants and wrote: “Kharchin officer Khaisan is an unflinching agitator. For many years and wherever he went to, be it Harbin, Kyakhta or Mongolia, he has promoted the idea of Mongolia’s independence and appealed to all Mongolian nationalities to unite. He might be the person who made the greatest of contribution to this cause (Mongolian National Revolution of 1911 is referred to – OB)”. (Архив Внешней политики Российской империи ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.645, с.165) The Bogdo khaan “approved” (Үндэсний төв архив Х.А74,д.1, х.н.823, н.2) when the Ministry of Interior inquired if it would be possible to allot to gung Khaisan, its senior officer, a plot of land for living in an area covering 6 guard posts from Uyalga to the east of the Tsagaan us post in west of Khyakhta.

THE CULMINATION OF THE MONGOLIAN NATIONAL REVOLUTION OF 1911 OR THE ENTHRONEMENT OF BOGDO JEBTSUNDAMBA KHUTUKTU AS EM- PEROR OF MONGOLIA ON 29 DECEMBER 1911

The Mongols formally proclaimed their independence on 29 December 1911. It was the culmination of the struggle they were waging at the initiative and under the leadership of the eighth Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu to get independent from the Manchu Ching state. (Үндэсний төв архив Ф.388, д.2, х.н.33 64 дэх тал)

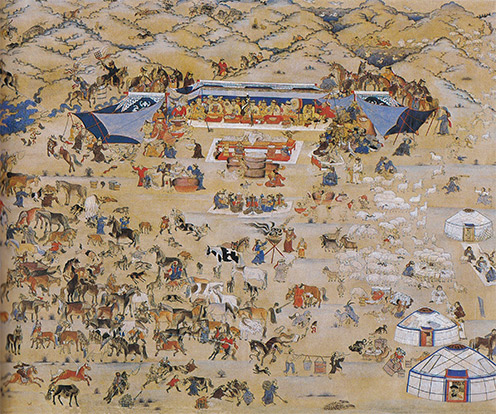

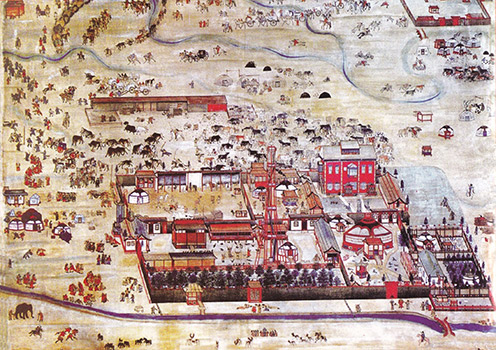

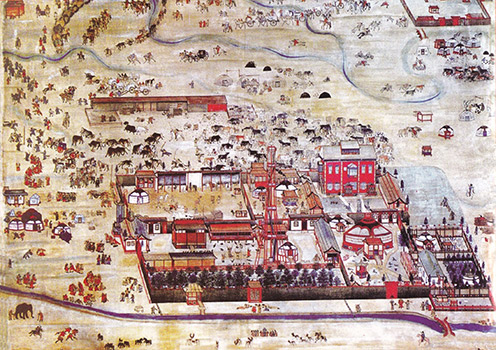

State Yellow Palace

The ceremony was held in a large, over ten lattice - wall gher covered with yellow silk with its ridges covered and sewn with blue silk and decorated with ornaments, nine types of jewels and seven kinds of offerings. (Богд хааны 2000: 59)

The Provisional Administrative Office of Khuree Affairs set detailed rules of procedure for the ceremony of elevating Bogdo to the throne as the Emperor of Mongolia. (Үндэсний төв архив Ф.А3, д.1, х.н.2, 16 дахь тал)

“The princes and chuulgan dargas of the five Khalkha aimaks, commanders, many zasags, khutuktus and khuvilgaans, shanzodba and da lamas, nobles, officials and taij - all arrived at Ikh Khuree.” (Монгол Улсын 1992: 9)

Time: The great ceremony of the enthronement started at the horse hour or 11 hours 40 minutes, which was found to be a very auspicious time (Котвичийн 1972: 102) and lasted until sun-set or about 5 p.m. If the ceremony continued, as it was said, from 11.40 a.m. to about 5 p.m (Харбинская газета “Новая жизнь” 4 Января 1912 года), it, then, lasted over 5 hours.

Venue: According to G.Navaannamjil (1956: 56), who attended the event, the state palace was a large, over 10 - lattice felt gher covered with yellow silk, with its ridges covered and sewn with blue silk and embossed with traditional and religious designs like nine precious jewels and seven offerings, set up in an empty space between Dechin Galba temple with a golden roof located inside Bogdo palace and Dorjvavaaran temple, the yellow fence of which had been extended to the north to make more space. The yellow state gher - palace was located in the vicinity of what now is Mongolian National University. Bogdo khaan, accompanied by his queen, proceeded to the state gher - palace from his two story winter palace (The Palace is said to have been built by Russians for the Bogdo khutuktu) on the bank of Tuul river.

The arrangement for the ceremony to start in the state gher - palace and continue with the offering of the mandala in the Tsogchin temple and end in the state gher - palace, was, perhaps, to imply the concord between the state and religion and the priority attached to state customs. (Гомбосүрэн 2005: 25)

The State Great Ceremony

In Ovgun bicheechiin ouguulel (Reminiscences of Old Clerk)’by G. Navaannmjil (1956: 59): “...there were so incredibly many people gathered in front of the large gate of the State Yellow Palace. Princes, officials, khutuktus and lamas in their official headware, jackets and variegated deels were standing in files the sound of firing by three cannons heard coming from the vicinity of the temple up.

When the Bogdo and Tsagaan dari came, all those gathered kowtowed and became quiet. Bogdo and his consort were sitting in a beautiful Russian yellow four-wheel carriage flying a golden flag. Eight attendants and lamas were carrying and leading the carriage. Before it high ranking lamas and escorts were marching in file. Two to three princes in black and wearing swords in red sheath were leading the group. Many guard troops, armed and in their fine uniform were walking in file along the sides of the road. When Bogdo and his consort came in through the central gate of the palace, all those princes and lamas followed them. All princes and lamas close to Bogdo were already in the gher - palace. Other princes were waiting in front of the state gher – palace”. (1956: 59)

As continued by Navaannamjil: “By noon was completed the preparation of a narrow wooden plank walks covered with yellow silk and extended from the door of the gher called Bogdo’s tugdam (tent-resident) located in the eastern section of the palace court to the back - rest seat with multi-layered cushion, placed on a high ceremonial platform with golden ornaments and supported by figures of four lions and located at the rear of the palace as well as to a gher - temple called Ochirdara”.

Bogdo khutuktu and ekh dagina, wearing expensive black fox-fur hats with thunderbolt buttons on top, colorful deel and speckled sable-fur jackets, slowly walked on the yellow silk walk prepared for the occasion. They were escorted by princes, soivon and donir. Three ceremonial parasols two with golden dragon designs and one adorned with peacock feather — were held above them from behind. The procession was led by a donir and a prince in black with a sword in a red scabbard. Bogdo and ekh dagina were supported with their arms by assistants and princes... Bogdo and ekh dagina, after visiting the Ochirdara temple, proceeded to the state gher - palace. Many khutuktus, khans, wangs, beel, beis, gung, zasag and taij, entitled to enter the palace, followed them. ... beis Puntsagtseren who used to be a Mongolian minister in Khuree, came out with a rather long document and announced loudly that a decree on distributing favors was issued. All the laymen and lamas, officials and clerks became silent and kowtowed. Beis Puntsagtseren began reading the decree. Bogdo was elevated as Bogdo, the sunshiny and myriad aged Emperor of Mongolia and the Tsagaan Dari as the Mother of the Nation. And the reign title would be ‘Elevated by Many’ and Ikh Khuree is to be called Niislel Khuree. And the state of Mongolia was established and a great ceremony was held.” (Навааннамжил 1956: 182-185)

When Bogdo khutuktu is elevated to the precious throne, all princes and lamas should kowtow three times and at that time soeogos would bring milk and tea, which soivongs shall recieve and offer to princes and lamas who shall take them and line up to kowtow and offer good wishes. Da lama Tserenchimed shall offer, while on his knees, blessing and kowtow three times. After the speech, The toast in honour of the Bogdo khaan was raised by Chin wang Khanddorj and gung Namsrai, the seal was presented by da gung Chagdarjav, the diploma was presented by Sain noyon Namnansuren, Commander Beis Gombosuren, Mandala by Tusheet khan Dashnyam, Setsen khan Navannerin, religious service was conducted by khamba nomun khan Puntsag and vice khamba Sodnomdarjaa, Buddha’s teaching was quoted by Manzushir Khutuktu Tserendorj and Jalkhanz Khutuktu Damdinbazar, stupa - by prince nomun khan Jigmeddorj, Erdene khamba Luvsantserendgvadogmi, symbols of seven precious jewels were presented by Shanzodba Badamdorj, mergen khamba Dembereldash, incantation for long — life - by da junwang Gombosuren and mergen wang Anand - Ochir and blessing and good wishes - by Da lama Tserenchimed. (Үндэсний төв архив Ф.А3, д.1, х.н.2, 16 дахь тал) Decree on distributing Bogdo’s favors to the public and those who made special efforts to contribute to the cause of establishing the Mongolian state was decided by government. By the decree on distributing favors, favors of 3, 6 and 9 lans were distributed to every old person aged 70 to 80, 80 to 90 and 90 to 100 years old respectively. (Богд хааны 2000: 62) After favors were presented, a banquet was held for the participants. Toasts were raised and blessings and good wishes were offered.

It was noted in a Secret History of the Khaan: “since the VIII Bogdo was invited into the Khalkha land, seasons of the universe have become more pronounced and supreme tranquility - perfect, no harms of foreign and domestic nature and no untimely plagues and diseases have occurred, no agitated words have been used, fruits have been abundant, merits have been acquired in abundance and good fortune and happiness have spread everywhere with the bodies and faces of the beings turned brilliant” (Богд Жавзандамба 126-96)

The following was written in the Secret History about the enthronement of the Jebtsundamba khutuktu as the Emperor of Mongolia: “. . . the Bogdo was blessed by all Gods and was praised for being capable of overcoming the obstacles of the past, present and future with his good fortune increasing like the flowering of seeds and flowers for eternity. He was named a benevolent Emperor elevated by many”. (Богд Жавзандамба 126-96) The enthronement of Bogdo Jebtsundamba on 29 December 1911 was described in the following way: “The Eighth Bogdo Jebtsundamba khutuktu was elevated, at his 43rd year, to the great precious throne of the Wielder of Power in both Church and State on the 9th day of the mid winter month of the year of iron pig of the fifteenth sixty-year cycle”. (Богд Жавзандамба 126-96)

Lavdovskii, Russian consul in Khuree sent to his Foreign Ministry a brief secret telegram under reference No. 1234, dated 16 December 1911, which informed: “Today Khalkha’s princes elevated the Gegeen as Emperor of all Khalkha during a festive ceremony attended by many”. АВПРИ ф.Китайский стол 143, Опись 491, д.644, с.388) Russian consul informed by this short letter a news to Russian government.

Lyuba, Russian Consul General in Khuree noted in his telegram of January 1912: “If the history of the last few years of Mongolia is ever to be written, it will underline, with a gratitude, the brave and resolute initiative of the eighth Bogdo Gegeen who accomplished what the bravest minds could not even dare to contemplate”. According to him the khutuktu was the person who led the movement that brought about the freedom Mongolia now enjoys”. (РГИА., ф.892, оп.3, ед.хр.127, л.1, АВПРИ, Фонд Миссия в Пекине, Опись 1, Дело 316)

Continuing his remarks which are now preserved in archival sources, he added: “Khutuktu is, without doubt, the person who led the event that led to the independence Mongolia is now enjoying” (Ibid., Delo 316). . . Khutuktu, at this historical moment, has risen to the height Mongolia was at one time of her history, and having felt the will and intention of his people, decided to cecede from China (Manchu – Qing state – O.B) and sought an assistance from great Russia”.

Consul Lyuba added: “At this historical time, the Khutuktu acutely felt the wishes and desires of his people and decided to sever Mongolia’s ties with China. Having reached the pinnacle of his power, just the way Mongolia used to enjoy at one time in her history, he sought assistance from Great Russia”. (Ломакина 2006: 64)

The Mongols have proclaimed their independence. They have been aided by the chaotic situation the Chinese found themselves in.

If the Bogdo Jebtsundamba Khutuktu could become an object of veneration of the Mongolian national religion before 1911, he, surely became, after the National Revolution of 1911, not only spiritual but also political leader, a ruler of the Mongols, in the true sense of the word. He is the father of the national revolution which marked the revival of the Mongols.

It is a day Mongolia restored her statehood and proclaimed formally to the world at large her independence and sovereignty. I view this action a special and historic event in the life of the Mongols in the last 300 years. It is appropriate to view this day as the day when the foundation of the state established by the Chinggis khaan of Mongolia was restored.