Munkhtsetseg

Javkhaajav (mong. Жавхаажавын Мөнхцэцэг)

Text in English

wurde 1967 in "Ulaanbaatar" Hauptstadt der Mongolei geboren. Sie absolvierte ihr Kunststudium 1987 an der Hochschule der Bildende Künste in Ulaanbaatar. Danach geht sie nach Russland um weiter zu studieren. Von 1989 bis 1993 hat sie Akademie der Bildende Künste und Theater in Minks Hauptstadt von Weißrussland (Seit 1991 ist das Land ein eigenständiger Staat) studiert. Sie lebt in Ulaanbaatar mit seinem Mann Erdenebayar Monkhor, der auch ein internationaler anerkennte Kunstmaler ist.

Einzelausstellungen

2009 "The Silence of Healing at the Edge of the World", Teo + Namfah Galerie, Thailand.

- "Blue Sky die sich in der Nord-Face", Striped - Gallery, Tokyo, Japan.

2004 "Haus der Frau" Einzelausstellung Kunstgalerie von UMA (Union of Mongolian Artists), Ulaanbaatar.

1999 "Humhiin ordnii zuud", Einzelausstellung, Grant von "MFOS" Soros-Stiftung, Art Gallery, Ulaanbaatar.

1996 Einzelausstellung, Deutschland Botschaft, Ulaanbaatar.

1995 Einzelausstellung Kunstgalerie von UMA, Ulaanbaatar.

Zwei Personen Ausstellungen

2004 "Indiana Memorial Union" Galerie, Einzelausstellung. Bloomington, USA.

2003 "E & M" Einzelausstellung, Grant of Arts kommune der Mongolei, in Ulaanbaatar.

2000 "E & M" Nomad Kunst - Galerie, Ulaanbaatar.

Gruppenausstellungen

2010 "Smoke in the Brain" - "Red Ger" Gallery, in Ulaanbaatar.

2008 Taiwan-Fusing Biennale in Taiwan.

- Beijing International Art Biennale-3 in China.

2005 Beijing International Art Biennale-2, in China.

- Silk Road Contemporary Art Festival "Worth Ryder" Galerie, Berkeley, Kalifornien, USA.

2003 Die Beppu Asien Contemporary Kunstausstellung, B-CON plaza, in Japan.

2002 "Epic of Nomaden", Morgan Modern Art Museum, Korea.

2001 "Malerei" Som Arts, San Francisco.

- "Fortschritt der Frauen der Welt", internationale Ausstellung, Lobby des UN-Center, New York, USA.

2000 Rockville Abteilung Center Exhibition, Art Gallery Maryland, USA.

- "Neun Schatz" Ausstellung, Fraum Museum, Bonn Deutschland.

- "Schamane des Dschingis Khan"-Ausstellung in Seoul, Korea.

- Ausstellung der mongolischen Künstler, Beijing, China.

- "00-87"-Ausstellung, Kunstgalerie von UMA, Ulaanbaatar.

1997 Die Ausstellungen der mongolischen Künstler, Bonn, Deutschland.

seit 1995 "Frühling", "Herbst" Ausstellungen, Kunstgalerie von UMA, Ulaanbaatar.

1995 "Inter" Galerie, Seoul, Korea.

1994 Die Ausstellung der mongolischen Künstler, Tokyo, Japan.

1993 "The Women Artists" Ausstellung, Galerie Bosen, Deutschland.

Awards

1995 Preis der Union der mongolischen Künstler (UMA).

Webseite: www.artbayarmugi.com

Text in

English

Munkhtsetseg Javkhaajav

was born in 1967 in "Ulaanbaatar" capital of Mongolia. She completed her art studies in 1987 at the College of Fine Arts in Ulaanbaatar. Then she goes to Russia to study further. From 1989 to 1993 studied she the Academy of Fine Arts and Theater in Mink Capital of Belarus (Since 1991, the country successfully completed an independent state). She lives in Ulaanbaatar with his husband Erdenebayar Monkhor, who is also an internationally recognized artist.

Artists statment

For

me a (traditional Mongolian) woman's hair symbolizes her impressive

strength. Her face may not exhibit strength, but what is hidden, what

is behind the face, is strength.

When

an artist begins a Buddhist tangka, the first mark is a red vertical

line which divides the paper into ying and yang... When I'm almost

finished painting, I begin to think of one strong line. I find this

line in the painting. This line, inspired by Buddhist philosophy, is

not divisive or suggestive of summerty, but is about concentration.

Solo exhibitions

2009 “The Silence of Healing at the Edge of the World”, Teo+Namfah Gallery, Thailand.

- “Blue Sky reflected in the Northern Face”, Striped Gallery, Tokyo, Japan.

2004 "House of Woman" personal exhibition Art Gallery of UMA, Ulaanbaatar.

1999 Personal exhibition, "Humhiin ordnii zuud", Grant of "MFOS" Soros Foundation, Art Gallery, Ulaanbaatar.

1996 Solo exhibition, Germany Embassy, Ulaanbaatar.

1995 Personal exhibition Art Gallery of UMA, Ulaanbaatar.

Two person exhibitions

2004 Personal exhibition, Indiana Memorial Union Gallery, Bloomington, USA.

2003 "E&M" exhibition, Grant of Arts counsil of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar.

2000 "E&M" Exhibition in Nomad Art Gallery, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

Group exhibitions

2010 "Smoke in the Brain" - "Red Ger" Gallery, Ulaanbaatar.

2008 Taiwan-Fusing Biennale in Taiwan.

- Beijing International Art Biennale-3 in China.

2005 Beijing International Art Biennale-2 in China.

- Contemporary Silk Road Art Festival, "Worth Ryder" Gallery, Berkeley, California USA.

2003 The Beppu Asia Contemporary Art Exhibition, B-CON plaza, Japan.

2002 "Epic of nomads", Morgan Modern Art Museum, Korea.

2001 "Painting" Som Arts, San Francisco.

- "Progress of the world's women" international exhibition, Lobby Center of UN, New York, USA.

2000 Rockville department center exhibition, Art Gallery Maryland, USA.

- "Nine treasure" exhibition, Fraum Museum, Bonn Germany.

- "Shaman of the Chinggis Khan" exhibition Seoul, Korea.

- The Exhibition of Mongolian Artists, Beijing, China.

- "00-87" exhibition, art Gallery of UMA, Ulaanbaatar.

1997 The Exhibitions of Mongolian Artists, Bonn, Germany.

since 1995 "Spring", "Autumn" exhibitions, Art Gallery of UMA, Ulaanbaatar.

1995 "Inter " Gallery, Seoul, Korea.

1994 The exhibition of Mongolian artists,Tokyo, Japan.

1993 The Women Artists Exhibition, Bosen Gallery, Germany.

Awards

1995 Price of Union of Mongolian Artists (UMA).

Website: www.artbayarmugi.com

"From The Heart Of Mongolia" By Ian Findlay-Brown

"From The Heart Of Mongolia" By Ian Findlay-Brown

Copyright © Ian Findlay-Brown 2009

When

the communist party gained control of Mongolia in 1921, under the

direction of the Soviet Union, the eradication of Mongolian traditions

and cultural life was swift, brutal, and all consuming. The great

purges of the 1930s saw the destruction of hundreds of monasteries

during which tens of thousands of monks were killed along with

innumerable intellectuals and ordinary people. The cost of ‘progress’

under an oppressive collectivization and class struggle in reshaping

the country into a 20th-century ‘model’ communist state was almost

complete isolation from the rest of the world. And throughout all the

changes (social, cultural, political, and educational) the loss of

identity was intensely felt among Mongolians. (1)

“The great

losses for Mongolians are the great painting traditions of the 17th

century and their philosophy of life,” says Tsendsuren Narangerel,

painter and dean of the decorative art department of the Fine Art

Institute of Mongolia in Ulaanbaatar. “The philosophy of the Mongolian

is their nomadic way of life and respect for nature and the earth. The

worst is that Mongolians not only lost their national art but also the

pride of their culture during the Soviet period.” (2)

For

artists the thirst for new identities has been profound since the

advent of democracy, in the early 1990s. This has informed the best art

made by many of Mongolia’s finest modern artists, many of whom were

educated either at art schools in the Soviet Union or in former Eastern

Bloc countries such as Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia (the Czech Republic

since 1993). At these art schools, as well as Mongolia’s pre-1990s art

institutions, socialist realism dominated the students’ curriculum. (3)

Changing

course has not been easy, especially for older artists. Munkhtsetseg

Jalkhaajav, who is 42, is not one of these. For her, studying art under

the socialist system at the Art Institute in Ulaanbaatar, from 1983 to

1987, and at the Academy of Fine Art and Theater, Minsk, from 1989 to

1993, was so frustrating that she left before graduating. This act

underscores her resolute nature. “During the communist time in Mongolia

and Russia, I only studied good technique and color,” she says. “But

there was not any heart in the teaching.” (4)

Munkhtsetseg

Jalkhaajav was born in 1967 in Ulaanbaatar where her early painting

studies were dominated by a Soviet art curriculum, which she says was

“little more than propaganda.” What she wanted was an education in

which the richness and vitality of Mongolian cultural traditions and a

modern visual sensibility could be combined to represent both her own

psychology and her observations on a rapidly changing society. At the

same time, she wanted to make art that possessed “a physical presence,

colors that are typically Mongolian, and a geometry to the features

that comes from traditional culture. I also wanted a stillness in my

art that reflects something of the stoicism of nomadic Mongolian

culture.”

Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav, as a painter and a woman,

believes that Mongolia’s new artistic vision should also heal

emotionally and spiritually. This has always been important to her, but

not always easy. Some of the challenges she has faced in her healing

process are clear in the paintings, works on paper, and soft sculptures

that make up the exhibition The Silence of Healing at the Edge of the

World. The pain of an emerging democracy and the dislocation of

cultural traditions are deeply felt. To address this artists need to

make new art to reflect this altered society. Munkhtsetseg’s art does

this exceptionally well.

The process of healing only became

possible for Munkhtsetseg after her return from Russia, when she

witnessed how democracy and freedom of expression were not only

altering Mongolian society but also changing individuals’ hopes. Today,

she notes, there is refreshing contemporary art that represents true

Mongolian aspirations and self-expression and that it is not

propaganda. Now that there is freedom to make art in whatever way one

desires, social thinking has moved from the collective to the personal.

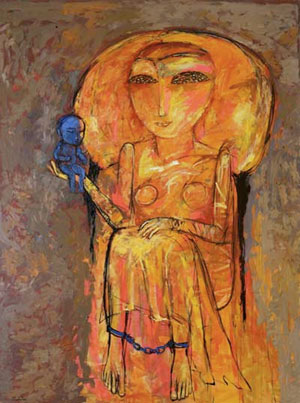

Munkhtsetseg

found her subject in women -- steely, bare-breasted women -- who

represent a rejection of totalitarianism’s puritanical propaganda in

which women, even though at the forefront of society, never appear to

be equal to men. These women, carefully constructed in the artist’s

mind, are then deconstructed on canvas to represent women’s spiritual

freedom and their relationship to the world around them in all its

complexity. Women in Mongolia, Munkhtsetseg notes, have always been

equal and this is why she doesn’t try to take a feminist point of view.

“I just express what I think and feel. It is up to the viewer to

interpret what they see. Mongolians have always respected women as

equals,” she says. “Women have the right to rule the household and the

state. When men, in the past, went to war, women controlled everything.

In traditional life men had to listen to women. So all my paintings

represent the power of women.”

Woman as her central subject has

given Munkhtsetseg the opportunity to create an uncompromising

narrative through which to explore questions of spirituality, birth and

death, female sexuality, personal disappointment, and motherhood. To

examine these she uses numerous symbols from Mongolia’s rich cultural

heritage. The birds, clothing, children, traditional Mongolian

medicine, legends and myths on the origins of the world, humankind’s

relationship to nature and animals, and the striking traditional

hairstyle known as ehkner us, which means ‘married woman’s hairstyle,’

all inform her

figurative art, recent abstractions, and representational collages and drawings.

The

power flowing from Munkhtsetseg’s bold figures is in stark contrast to

her slight physical presence that hides a steely determination. She

observes and listens intently. Her slim hands exude an appealing

combination of fragility and strength. She wields a brush thick with

paint and tears paper for her collages with equal passion. When the

results are not to her liking, she simply begins again, working until

she is satisfied. When she is happy with the results, she is never

boastful. Indeed, Munkhtsetseg (“Mugi” to her friends) has a sense of

humility about her that is memorable. For all her accomplishments,

since the mid-1980s, she says simply, “It is only during the past five

years that I have considered myself an artist. Before, I only saw

myself as an artist in training.”

Munkhtsetseg’s portraits of

women are not gentle or refined or timid. They are tough, highly

textured, boldly colored studies of characters that exude powerful

emotions. While she speaks clearly to her own culture, she is also

addressing womankind far beyond it. Her commanding protagonists are by

turns also absolutely still and animated by tension in their fluid

geometry. This is accentuated by her use of strong blues, reds, browns,

and greens. This is especially true of her works in which children and

giving birth sit at very heart of her narrative.

One sees this

in such works as Endless Desire (2008), representing the reality of

multiple generations. Reborn (2008), Birth Myth, and Nexus (both 2009)

project the innocence of the mother/child relationship. The dramatic

Spirit of Survival), in which the artist uses a rich green, not only to

emphasize the importance of children as a physical reality but also, as

they sit on leaves that are affixed to the woman’s hair, as dream.

These works confirm some of the major strengths of her art such as her

love for textures and colors.

While these works form a

collective memory of both the place of children and their

life-affirming innocence in the life of a woman and society, they also

show the power and spirituality of womanhood. This memory is

strengthened by traditional and modern imagery and Munkhtsetseg’s own

personal experience of the loss of a child. “The relationship between

tradition and modernity is strongly expressed in her work. One can feel

her soul and energy and power,” Tsendsuren Narangerel, “Children

symbolize the nexus of life. They represent personal love. I have a

son. But I have experienced the loss of a child at birth,” Munkhtsetseg

says. “After my son, I had a miscarriage and could not have another

child, which has affected me deeply. This is why my works are deeply

personal and why my works have helped to heal my spirit.”

While

Munkhtsetseg cites such artists as Kiki Smith, Hans Arp, Louise

Bourgeois, and Yayoi Kusama, as well as the Mongolian sculptor

Zanabazar (1635—1723) as inspirations, she says that none are

influences. The artist says that when sees the work of other artists,

“It makes me reflect on myself because it is very difficult to be

oneself.”

Beyond traditional Mongolian culture and symbolism she

notes that theater design, mural art, and Russian icons have also

played a part in changing her art over the past two decades. And while

her oeuvre is dominated by both figurative and abstract work, she sees

herself merely as an artist, “neither an abstract artist nor a realist.”

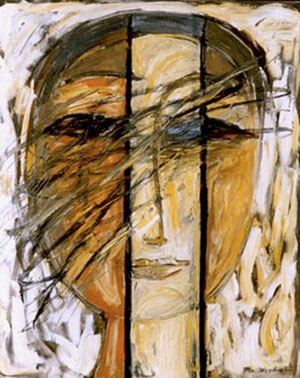

If

Munkhtsetseg’s art is neither abstract nor realistic, there is

certainly a case for seeing much of it as tending toward the surreal.

Her symbolism and how she uses it within her paintings and collage

reinforces this idea. Munkhtsetseg has carefully constructed her women

over the past two decades, beginning with a concentration on hair, then

the eyes, the ears, the legs, the hands, and then the breasts; while

the women are often semi-naked, there are rarely erotic elements in her

pictures.

Such careful development was also a revelation for the

artist. “When I had learned to paint all the physical elements of the

body, it felt like my painting had gained a soul,” she says. “It felt

like a living being was being born through the painting and it became

more spiritual as my work moved from the mere physical representation.”

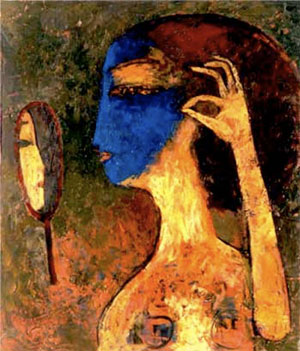

Birds

-- including magpies and skylarks -- in traditional Mongolian medicine

are symbols of one’s heartbeat, and are central to the surreal drama

that is taking place in such works as Pulse (2008), Sacred Offering

(2009), The Gift (2009), and Lung, (2008). In Sacred Offering

Munkhtsetseg’s birds rest in the luxuriant hair of the alien blue-faced

woman, a timeless face, one that reminds the viewer of religious

figures in ikon painting and ancient mural art. This blue – an

important color for Munkhtsetseg, which come from the influence of

Zanabazar -- is also found in her moving work entitled Gazing (2009).

In Pulse the birds are linked to the woman’s veins and are either

drawing blood from her or taking her pulse. In Tangling Hair (2009) the

birds appear to nest in an ornate hairstyle suggestive of tangled

branches. Other symbols of heart and bird at the bottom of the painting

-- to the left and the right -- add to the surreal image.

“In

nomadic culture Mongolians believe that birds are symbols of good and

bad news and they can also be used in fortune telling,” she says.

“Birds have been used in Mongolian and Tibetan traditional anatomy for

centuries. I am inspired by this as birds in my art represent healing,

transfiguration, becoming pregnant, and the pulse of life.”

That

Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav’s art is about the power of women --

physically, emotionally, and spiritually -- is clear. With each new

series she builds upon earlier work to make these points more fully as

she matures as an artist. Her use of hair, for example, speaks not only

to female beauty and the power of women, but also to the spiritual and

humanity’s connection with animals. “In traditional Mongolian culture,”

she says, “the hair holds the woman’s spirit and soul. I believe in

this. But hair also represents the abstract cosmic world.”

She

addresses this in her paintings, collages, and drawing through a drama

of color and lyrical line. In Hair Performance: I am Protected (2009)

the hair flows from the head of nude woman on her back, at the top of

the picture, as if it is seeking the earth. In the delicate line

drawing Hair Performance: Hair Ceremony (2009) and the oil Hair

Performance – Roots (2009) the nude figures sit, legs open, at the top

of the painting, their hair flowing gently to the ground seeking to

root itself in the earth. In the oil Nowever (2002), the hair of three

women streams across the picture place taking on the rhythm of a

landscape.

In the early works On The Mountain (2000) and

Messenger (2002) hair is clearly shown as a metaphor for physical

power. The ehkner us hairstyle of the women is made in the image of

powerful goat horns. But here Munkhtsetseg is not only showing power,

but also connecting humankind with the animal world and showing just

how central this is to all life.

Munkhtsetseg is speaking not

about sexuality – though it is certainly an element in her work – but

about how people are rooted to the earth and connected to all natural

and cosmic power. She says that this is especially true about women

whose grasp on matters of life and death, nature and natural

relationships are often more grounded than men’s.

“Women give

birth to men,” she says. “The traditional concept of hair is that it

holds the spirit and soul. So in these works the women are seeking

their connection to nature as the hair seeks to be rooted in the

ground. When the hair is being cut, as in my Liberation Series No 3

(2008) it can be compared to meditation so as to release the mind and

soul of pain.”

Further enhancing the surreal in her work is how

she uses aspects of traditional Mongolian medicine, its spells and

rituals to look beyond the surface of the body. That birds and animals

feature so prominently in her art is not mere affectation. It is

something that is thoroughly of Mongolian as it the belief that animals

can heal humans both physically and mentally.

For Munkhtsetseg

the body is a whole cosmic unit, not merely separate external and

internal worlds to be treated separately: They speak as one in the

natural order of life. “I used to draw organs individually, but now

when I draw them it is as a whole, as an integral part of the whole

body,” she says. “Now, in my art the body has a spirit or a soul,

before it was bits and pieces.”

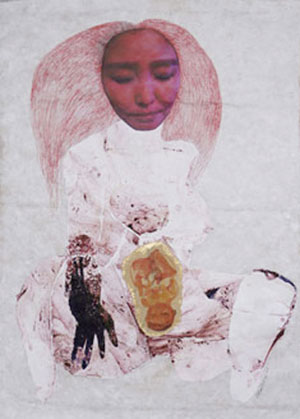

Munkhtsetseg’s collage technique

is very different from that used in her paintings. In her paintings the

spirit of her figures emerges from beneath the brush, but in collage

she says, “When I create a figure I do it by tearing the paper I use my

hands and it feels like the paper itself creates the figure.”

She

feels that in her collages she can express the ideas of traditional

Mongolian medicine more strongly as she can use ready-made materials

like book pages from medical texts. “For me, it is important that I

make many abstract sketches in advance so that the sketches lead to the

final creation. I can then show how spells and treatments can be used

to change the gender of a child in the womb, using sheep’s wool and

goat’s wool, making a thread of it, and tying it around the body as the

person is reading a mantra.

The collages, in which she utilizes

handmade paper, cloth, pencil, ink, oil, pages from anatomy books, and

recently, photographs, have added immeasurably to Munkhtsetseg’s

artistic vision. There is a unique and disturbing strength to these

works. She has chosen not to look at the external beauty of the female

body, but to highlight the internal. It is inside the body that the

struggle for life takes place, within the pulsing of organs and

breathing skin, from the constant beating of the fragile heart to the

life-giving blood that hurtles through the veins. It is here that

Munkhtsetseg’s cosmic reality takes full flight. Her fine collage

series Tearing Language (2009) not only highlights the cosmic, but also

speak to us as her gateway to the soul.

Works such as Tearing

Language No 2, No 9, and No 13 exemplify just how well Munkhtsetseg

constructs the cliché of the sensual naked woman shown from behind and

then how well she deconstructs it. Her images are from the seductive

poses made by commercial artists who cater to a market that demands

illusion, not truth. Munkhtsetseg understands very well, as her

dramatic paintings show, just how often truth and illusion collide and

become tortured visions.

Tearing Language No 9 is a singularly

powerful example of her collage art. Here we are aware of the muscle,

sinew, and organs and we sense how they work together. What the artist

is clearly saying to the viewer is that beyond the body’s soft skin

lies a confusion of life-giving organs that are not so pretty to look

at. While she often reveals the structure of bones and joints, here she

uses the long plait to become the spine: This is her only gesture to

female beauty. At the same time, she shows us that the organs of our

system have to be healed before we can become whole again.

Munkhtsetseg’s collages reinforce the reality that healing begins for

us on the inside.

Using collage also allows her to show other

aspects of her thoughts and beliefs, from examining shamanistic beliefs

to articulating the simplest gesture of a child. The heavy impasto of

her paintings gives way in the collages to a rougher quality, with a

touch of spontaneity. This makes for a different narrative tone and

perception in her oeuvre. It is as if she is peeling back the skin of

her emotions to let the viewer inside her very thoughts on life, birth,

death, and personal loss.

Although her collages are highly

controlled creations and emotionally and intellectually on a different

artistic reality than her paintings, this does not mean to say that

they are always austere. Far from it, there are touches of wry humor,

too.

Munkhtsetseg’s surreal touch in such paintings as Pulse

(2008), Spirit of Survival (2009), and Sacred Offering (2009) is

carried further in the bird image that is Tearing Language No 5.

(2009). Here Munkhtsetseg displays both fine drawings skills and a

vivid imagination. The bird is realized as an illustration in an

anatomy book about strange beings. The inner workings of the bird are

revealed in magnificent detail: It is part animal, part human. The feet

are human legs and the wings are outstretched human hands; both are

skeletal, the tendon holding the muscle to the bone that adds a

peculiar strength to the skeletal hands. A headless male torso, arms

outstretched, hands clasp a length of human hair, emerges from the

bird’s abdomen. This birth image, which reminds one of mythic

human/animal connections, adds vividly to this surreal work.

There

is something disturbingly obsessive about this work. But then

Munkhtsetseg’s art is not meant to be a pleasant interlude among

sentimental images. It is meant to confront, boldly and questioningly.

In this work she achieves a sense of drama so different from that in

the narrative of her paintings. At the same time, the entire Tearing

Language series makes us realize that her art, like her life, is far

more substantial than the sum of its parts. She makes us aware that

life is also more than simply breathing, loving, and constant struggle.

Such

notions are further examined in Munkhtsetseg’s recent soft sculptures:

I don't tell where I am from, Path, Body as Tangled Hair in

Intermission Space, and Enjoyable Pleasure (all 2009). “I wanted to see

some aspects of my painting in three dimensions,” she says. These works

are another significant step in her exploration of healing through art:

they speak to children, the emotional pain of loss, physical trauma,

and identity.

Although Munkhtsetseg never studied sculpture, she

began to consider it after seeing sculptures by the Japanese artist

Yayoi Kusama in New York in 2001. But her inspiration as a sculptor

also has its roots in Zanabazar’s art. Since childhood, she has admired

his Tara sculptures. Munkhtsetseg’s soft sculptures of sewn silk and

felt, however, are far from these influences. It is clear in these

works that her training in theater design comes into play.

Munkhtsetseg

first makes drawings, then carefully follows these as she sews (a skill

she learned as a young woman). It is a long process. “Sometimes I get

lost along the way. But my mistakes give me good ideas.” Sewing also

gives her the “freedom of working with soft materials. It helps me to

develop my images.”

Monglians love to make things with silk,

including special traditional clothes, deel, for children. “I made it

for my son in 1992. I have always wanted to make something using silk,”

she says. “Sometimes, when I finish a painting, I feel that I have not

expressed all my emotions. So sculpture becomes another emotional level

of my narrative of the woman/child relationship.”

Path, a

silver-colored sculpture of a seated, forlorn faceless baby with its

umbilical chord snaking out from its body, is a powerful work that

suggests the terror of the innocent. This is also true of the

goldcolored I don’t tell where I am from. The multi-armed child is

seated with hands covering eyes, ears, and mouth in the manner of ‘I

have nothing, see nothing, and say nothing.’ Such works have their

origins in paintings such as Spirit of Survival, Nexus, and Birth Myth

(all 2009).

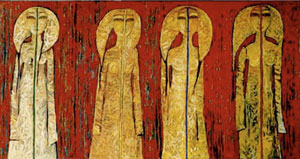

While sculptures such Path and I don’t tell where I

am from suggest something of the pain of birth, they also allude to the

artist’s own personal loss. This is not the case with her sculptures

dealing with contortionists as in silver and gold Enjoyable Pleasure

and in the bold-red group in Body as Tangled Hair in Intermission Space

(both 2009). These two works, with their origins in works such as

Reborn (2008) and Pattern of Nature (2009) speak more to struggle and

survival than birth pangs. Munkhtsetseg’s contortionists appear to

suggest that struggle in life is a constant, a necessity for change and

healing.

“When I am making soft sculpture,” says Munkhtsetseg,

“I feel that I am creating a human body by the Lunar calendar. In the

Lunar calendar the human soul exists in different organs every day. For

example, first the soul exists in the feet; then the soul exists in

knees, and so on.”

Mongolian artists feel their cultural loss

deeply. How do a nation and its people heal in the midst of change?

This is a difficult question to answer, according to Tsendsuren

Narangerel. “When I was abroad, I saw a lot of Mongolian cultural items

in museums. I felt sad about that. The loss of culture is incurable.

Which also means spiritual and material loss,” he says. “We should not

repeat this mistake. For that we have to work hard and to create art.

So in that way art heals.”

Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav’s rich

personal narrative is certainly an important statement in the healing

process. Looking at a broad range of her art made since the late 1990s,

one realizes always that for her art is as much about healing as it is

about the art itself. Through this the pain of her loss as a woman is

slowly being alleviated. Her vision is becoming stronger. Her voice is

more confident. Despite this she continues to feel doubtful. It is a

necessary doubt, one that drives her forward to heal and be healed.

“Each year,” says Munkhtsetseg, “I feel I become more of a complete

artist. But even so I always find myself feeling that there is

something missing.” (6)

Notes:

1.

Baabar (Bat-Erdene Batbayar), History of Mongolia, Cambridge, England,

The White Horse Press,1999. The editor Christopher Kaplonski, notes in

his Editor’s Preface, “One of his [Baabar’s] most famous writings, Buu

mart! (Don’t Forget!), written in Moscow in 1988, but not published in

Mongolia until 1990, “was a call to remember Mongolian traditions and

identity in the face of socialism.”

2. Quotations from Tsendsuren

Narangerel are taken from the author’s interview with him at the Fine

Art Institute of Mongolia in Ulaanbaatar on April 17, 2009.

3. This

is an extended and updated version of an earlier essay. See Ian

Findlay, “From The Heart Of Mongolia,” Asian Art News, Volume 19 Number

3, May/June 2009, pages 72—77.

4. Unless otherwise stated quotations

are from interviews with Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav conducted by the

author in Ulaanbaatar between April 14 and April 17, 2009.

5.

Zanabazar (1635—1723), also know as Ondor Gegeen, was the First Bogd

Gegeen. He is considered to be the greatest artist of Mongolia.

6.

The author thanks Ms. Delgermaa Ganbat, advocacy Program Coordinator,

the Arts Council of Mongolia, and Ms. Ts. Yuno for their generous help

with interpreting while in Ulaanbaatar.

Copyright © Ian Findlay-Brown 2009

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010. Artists: J. Munkhtsetseg (installation) M.Batzorig (graphic), Bu.Badral (video art & painting), Ts.Ariuntugs (video art & installation), Kh.Batbaatar (painting), D.Davaanyam (photo art), B.Nandin-Erdene (collage), A.Bayarmagnai (painting), D.Bayartsetseg (graphic, performance), D.Uuriintuya (mongol zurag - painting).

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010. Artists: J. Munkhtsetseg (installation) M.Batzorig (graphic), Bu.Badral (video art & painting), Ts.Ariuntugs (video art & installation), Kh.Batbaatar (painting), D.Davaanyam (photo art), B.Nandin-Erdene (collage), A.Bayarmagnai (painting), D.Bayartsetseg (graphic, performance), D.Uuriintuya (mongol zurag - painting).

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010.

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010.

Back

Munkhtsetseg

Javkhaajav

Munkhtsetseg

Javkhaajav

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010. Artists:

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010. Artists:  "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010 "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010 "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010 "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010 "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010 "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010 "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010 "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010 "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010 "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010 "Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010.

"Tarhin dahi Utaa" (Smoke in the Brain) Group exhibition in "Ulaan ger" (Red Ger) gallery, Ulaanbaatar 2010.